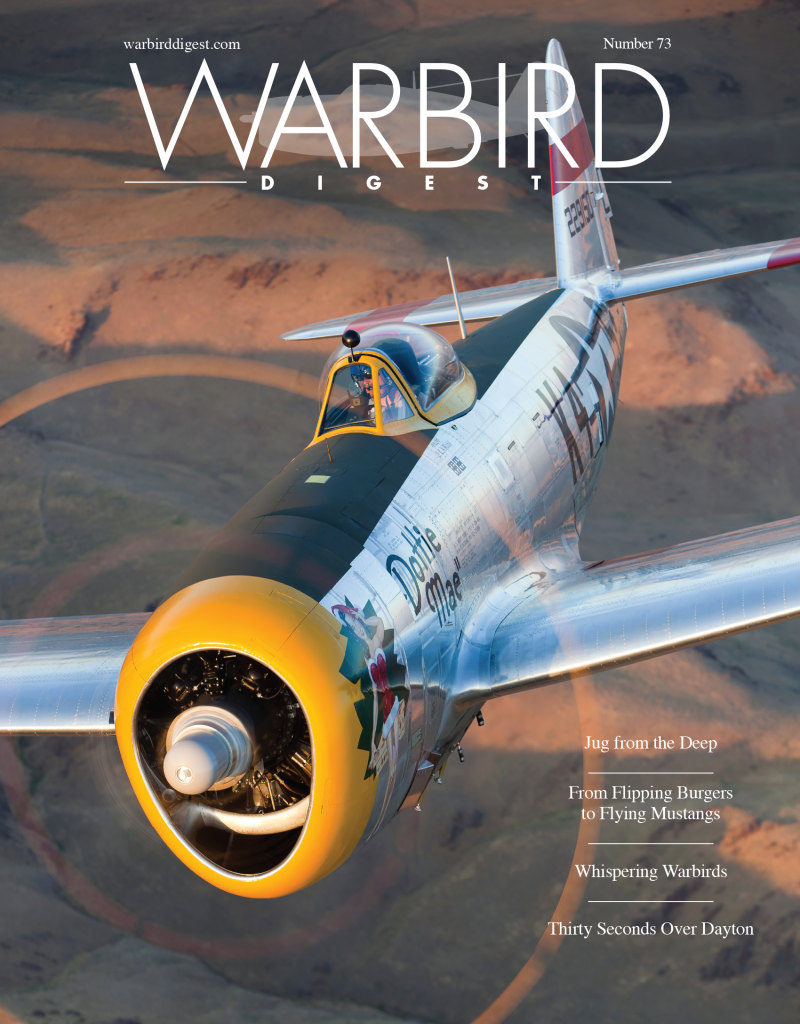

Warbird Digest has just received the December, 2020 report from Chuck Cravens concerning the restoration of the Dakota Territory Air Museum’s P-47D Thunderbolt 42-27609 at AirCorps Aviation in Bemidji, Minnesota. We thought our readers would be very interested to see how the project has progressed since our last article on this important project. So without further ado, here it goes!

Update

The newly-restored radio components arrived from John Castorina at Warbird Radios and permanent installation on the 5th Air Force, field-modified mounts has begun. The restoration technicians continue working hard on the wings, with new skin and wheel wheel completion the major tasks this month. Hydraulic plumbing and radio wiring is the focus of fuselage restoration.

Wing

The structurally complex wing remains the major focus of restoration efforts this month.

Wheel Wells

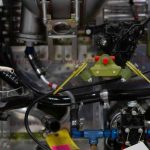

Fuselage Systems

The outward appearance of the fuselage doesn’t change much as all the myriad internal systems are installed and connected, but progress continues.

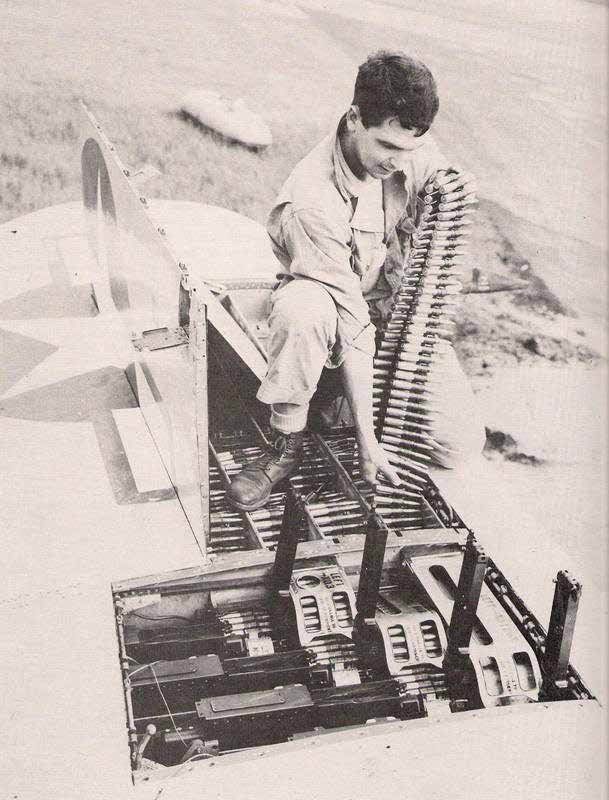

Browning M-2 Machine Guns

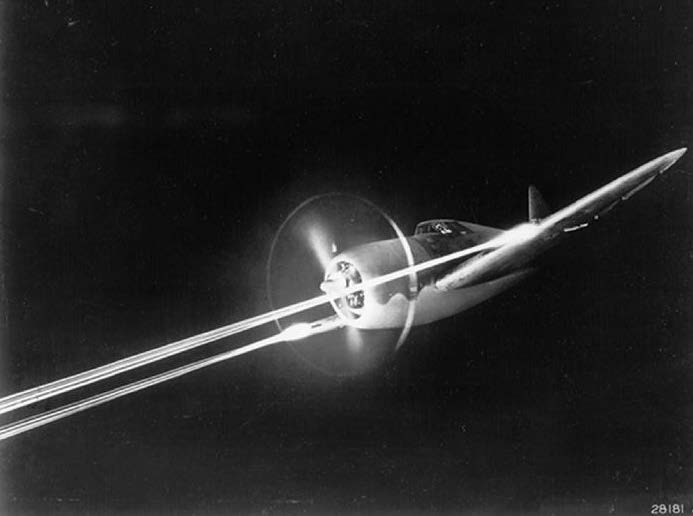

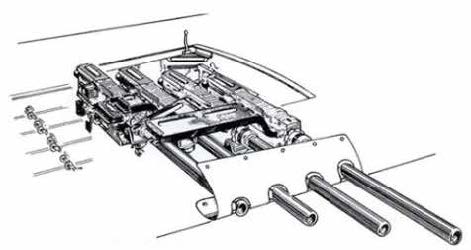

The Thunderbolt relied on a formidable array of eight .50 caliber machine guns for air-to-air combat and strafing. Most other US fighters used the same weapon, the Browning AN/M2 .50, but only carried 4 or 6 of these heavy machine guns.

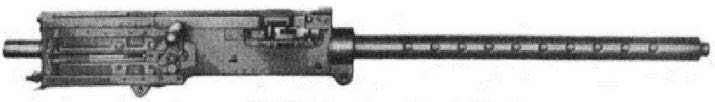

The Browning M2 heavy machine gun is a truly remarkable weapon. It is the second longest-serving weapon in the US military’s arsenal, after the M1911 semi-automatic pistol (another weapon designed by the prolific genius of gun design, John Moses Browning). Slightly upgraded versions of the M2 are still employed by over 60 countries worldwide. The M2 defined the modern use of the term heavy machine gun.

The origin of the Browning M2 dates back to battle conditions observed in the First World War. At this time the U.S. Army infantry and air service were armed with .30 caliber machine guns like the Browning M1917 on the ground, and the Lewis or Vickers gun on aircraft. Tanks, armored vehicles, and even an armored German aircraft (the Junkers J-1 ground attack aircraft) were introduced in WWI, and because of this it soon became apparent that there was a need for a more powerful round capable of penetrating armor better than the venerable M1 (30-06). General Pershing requested the development of a new machine gun with a caliber not less than .5″ and a muzzle velocity of at least 2,700 feet per second. John Browning went to work scaling up the M1917 machine gun for a heavier cartridge of his own invention. Browning scaled up the .30-06 round to .50 caliber (12.7-millimeter) initially for use as an anti-tank round and then adopted it for a new machine gun, the water-cooled M1921. The M1921 weighed 79 pounds without water and fired 500 rounds a minute. John Browning’s machine guns worked on the recoil-operating principle. The rearward force of expanding powder gasses pushes the barrel and bolt to the rear, and after a short recoil, the bolt is unlocked and the barrel stops. The bolt continues to the rear, and the feed mechanism feeds a round from a belt of ammunition. The bolt pushes the cartridge into the chamber as it is returned by a spring until it again joins the barrel. Unfortunately, Browning’s invention wasn’t ready until after the Armistice of 1918, too late for WWI combat. After Browning’s death in 1926, Dr.S.H.Green redesigned the M1921 creating a downward-ejecting common receiver design which could be modified to feed from the left or right. The new machine gun became the Browning M2. The right and left feed options would prove to be very useful in adapting the M2 to fighter plane gun bays, since the ammunition chutes would feed from the left on the left wing gun bay and from the right on the other wing. Colt started manufacturing the M2 in 1933. During WWII, US manufacturers from AC Spark Plug Co., to Frigidaire, to Guide Lamp, built nearly 2,000,000 .50 calibers.

The Browning .50 caliber was used in almost every US WWII fighter or bomber. The M2 began to be installed in US fighters in the 1930’s. Some versions of the Boeing P-26 “Peashooter” carried one .30 and one .50 caliber machine gun. The Navy Grumman F3F had a similar gun set-up. By the end of the 30’s, the P-40D carried two .50 caliber M2s in each wing. Combat experience showed the need for more firepower and the typical US fighter carried three .50s in each wing by about 1942. The P-47 carried four Browning AN/M2 .50 caliber machine guns in each wing in nearly all Thunderbolt models produced. Up to 400 rounds could be carried per gun, enough for 32 seconds of fire, but the ammunition load was often reduced to compensate for the carriage of bombs or external fuel tanks. Cooled by the aircraft’s slip-stream, the air-cooled .50 caliber (12.7 mm) AN/M2 was fitted with a substantially lighter 36-inch length barrel, than the M2s destined for ground use. The lighter barrels reduced the weight of the complete unit to 61 lbs. (23 lbs. Less than the 84 lb. ground version) and also had the effect of increasing the rate of fire. The shorter, lighter barrel in the aircraft version allowed the gun to cycle slightly faster because there was less inertia in the lighter moving barrel and bolt.

Originally, the Air Corps adopted the M2 with a 600 r.p.m. cyclic rate. But, as aircraft speeds increased, fighter pilots had less time to track and shoot. Therefore, Frankford Arsenal boosted muzzle velocity from 2,700 to 2,880 f.p.s.. The standard ball cartridge was the 709-gr. projectile atop 253 grs. of IMR-5010. Armorers experimented with various belting combinations, alternating ball, armor-piercing incendiary (API) and tracer. The M2 AP (armor piercing) round would defeat nearly an inch of face-hardened steel at 200 yds. Armor-piercing incendiaries (usually 647 to 662 grs.) were most useful against aircraft, as they could penetrate enemy armor and engine blocks, sever enemy airframe components, and ignite enemy fuel tanks [ref. Barret Tillman, The .50-cal. Browning Machine Gun—The Gun That Won The War, American Rifleman]. Seeing a Thunderbolt diving at you with eight .50s throwing a stream of fire had to be a terrifying experience!

And that’s all for this month. We wish to thank AirCorps Aviation, Chuck Cravens for making this report possible! We look forwards to bringing more restoration reports on progress with this rare machine in the coming months. Be safe, and be well

Be the first to comment

Graphic Design, Branding and Aviation Art