In this poignant piece, Warbird Digest’s Stephen Chapis recounts the all-too-brief fighter career of a young American hero during WWII. We hope this story helps his name and his story live on…

Tragedy Over Nagoya

by Stephen Chapis

On July 16th, 1945, members of the 506th Fighter Group fought their largest and most successful aerial engagement of the war. Tragically, one of their number did not return.

John Wesley Long Benbow was born on March 23, 1918, in Greensboro, North Carolina. He was the third of four children born to Charles & Majorie Benbow. After graduating from Greensboro High School in 1936, he was accepted to Guilford College, a Quaker institution, where he was a member of the boxing team. He later transferred to the University of North Carolina, but dropped out to join the U.S. Army Air Forces following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

On December 19th, 1941, John reported to the 64th Training Detachment at Woodward Field, a small airport near Camden, South Carolina. Ten days after he arrived, John broke his leg playing baseball, so he did not solo the PT-17 until March 11th, 1942. Once he completed Primary training, John went through Basic at Shaw Army Airfield (AAF) near Sumter, South Carolina. During his Advanced training at Spence AAF in Moultrie, Georgia, he was tapped to become an instructor himself, heading off to Maxwell AAF in Montgomery, Alabama to take the requisite courses. Upon completing his instructor-training in October 1942, he spent the next year-and-a-half training fledgling pilots; initially back at Spence, then at Dale Mabry AAF in Tallahassee, Florida, Fort Myers AAF, then Venice AAF, also in Florida. He logged hundreds of hours in AT-6s, P-47s, and P-39s.

While at Venice AAF, Benbow met William Lawrence and the pair became fast friends. According to Lawrence, he and Benbow walked into a Sarasota bank one day in early 1944 and one of the tellers, Margaret Coe, caught Benbow’s eye. Benbow nudged Lawrence saying, “You see that girl? I’m going to marry her!” They began dating and shortly thereafter they married on June 11, 1944. The Benbow family does not know the details of John and Maggie’s courtship and marriage, but there are numerous photos of them enjoying Florida’s beaches.

On October 21, 1944, as Benbow continued instructing at Venice and enjoying life as a newlywed, the 457th FS was activated at Lakeland AAF with Major (Maj) Malcolm C. ‘Muddy’ Watters commanding. The squadron was one of three that made up the 506th FG, a Very Long Range (VLR) Mustang unit destined to escort B-29s to targets in Japan. As the squadron commander, Watters was authorized to select Flight Commanders, and tapped Benbow, whom he knew from his time at Page Field, as ‘D’ Flight Commander.

At the time of activation, the 457th had a motley mix of P-51A/B/Cs & Ds, as well as four BT-13s. However, on December 21st, 1944, the squadron began receiving brand new P-51Ds. On February 15th, 1945, four days before the Battle of Iwo Jima commenced, the 506th FG was restricted to their post while they readied for deployment to that soon-to-be famous island bastion. The next day, John kissed Maggie for the last time and boarded a train bound for the west coast, where the group boarded the escort carrier USS Kalinin Bay (CVE 68) for the ocean voyage to Guam.

The 506th arrived on Guam on St Patrick’s Day 1945. Maintenance personnel immediately began readying the Group’s Mustangs at the Guam air depot; the fighters had also made the journey to the island aboard an aircraft carrier. On March 22nd, John made the following entry in his dairy, “Half hour test hop at Orote. Pretty good landing. Felt funny after having gone a month without flying. Glad to be back at it again.” The following day, Benbow celebrated his 27th birthday by leading a flight of four Mustangs up to Strip #4 on Tinian Island. The next day, they took a C-45 back to Guam and brought up four more P-51s. Upon arrival, they beat up the field with several low passes!

On March 28th, Benbow flew the first of his many Combat Air Patrols (CAP) in defense of Tinian and Saipan. These CAPs mostly consisted of droning through the skies monotonously for hours on end, but in his diary, he mentioned two incidents that broke the boredom. On April 2nd, he wrote, “Scramble and radar intercept mission. B-24s escorted by F6Fs and Corsairs. D Flight tangled wif [sic] and thoroughly whipped 2 Corsairs.” Four days later, as Benbow was turning off the runway following the afternoon CAP, his element leader, 2nd Lt Leonard J. Kloiber, slammed into the back of his Mustang. The impact sheared the tail off Benbow’s P-51, destroying the front of Kloiber’s fighter in the process. Thankfully, both pilots walked away without a scratch. John noted in his dairy, “Maggie was there beside me somehow during and after the accident when I needed her. She kept me cool and calm. I love that gal!”

Much to his chagrin, Benbow was not scheduled for the 506th’s first mission over the Japanese homeland on May 18th, and while he was set to go on May 24th, engine over-heating forced him to ground-abort. Finally, on May 28th, he was on the mission to strike Kasimagaura airfield, 35 miles northeast of Tokyo. After the mission, Benbow wrote, “Very tiring mission. Fairly successful. Everyone was too spread out and attack was uncoordinated. Landed at 1715, got skonked on beer and whiskey. Sweet letter from Maggie waiting for me.”

On June 11th, 1945, John received his first of two Air Medals for his actions over Kasimagaura airfield. However, this honor paled in comparison to this date also marking his first wedding anniversary. The note in his dairy said, “1st Anniversary today. Best year of my life.” Just a few weeks later, in early July, Maj Watters appointed Benbow as the Squadron’s Operations Officer.

On July 16th, VII Fighter Command issued Field Order #146 which tasked the 506th with strafing Akenogahara and Suzuka airfields on the main Japanese island of Honshu. Prior to this day, the group had scored 23.5 aerial victories in four engagements with Japanese fighters. At 1025hrs, 64 Mustangs from all three 506th squadrons launched from Iwo for the nearly four-hour flight to the target area. During this time, eight aircraft aborted for various reasons, and four each were assigned to cover the rescue submarine and navigator B-29, thus leaving 48 Mustangs to enter the target area.

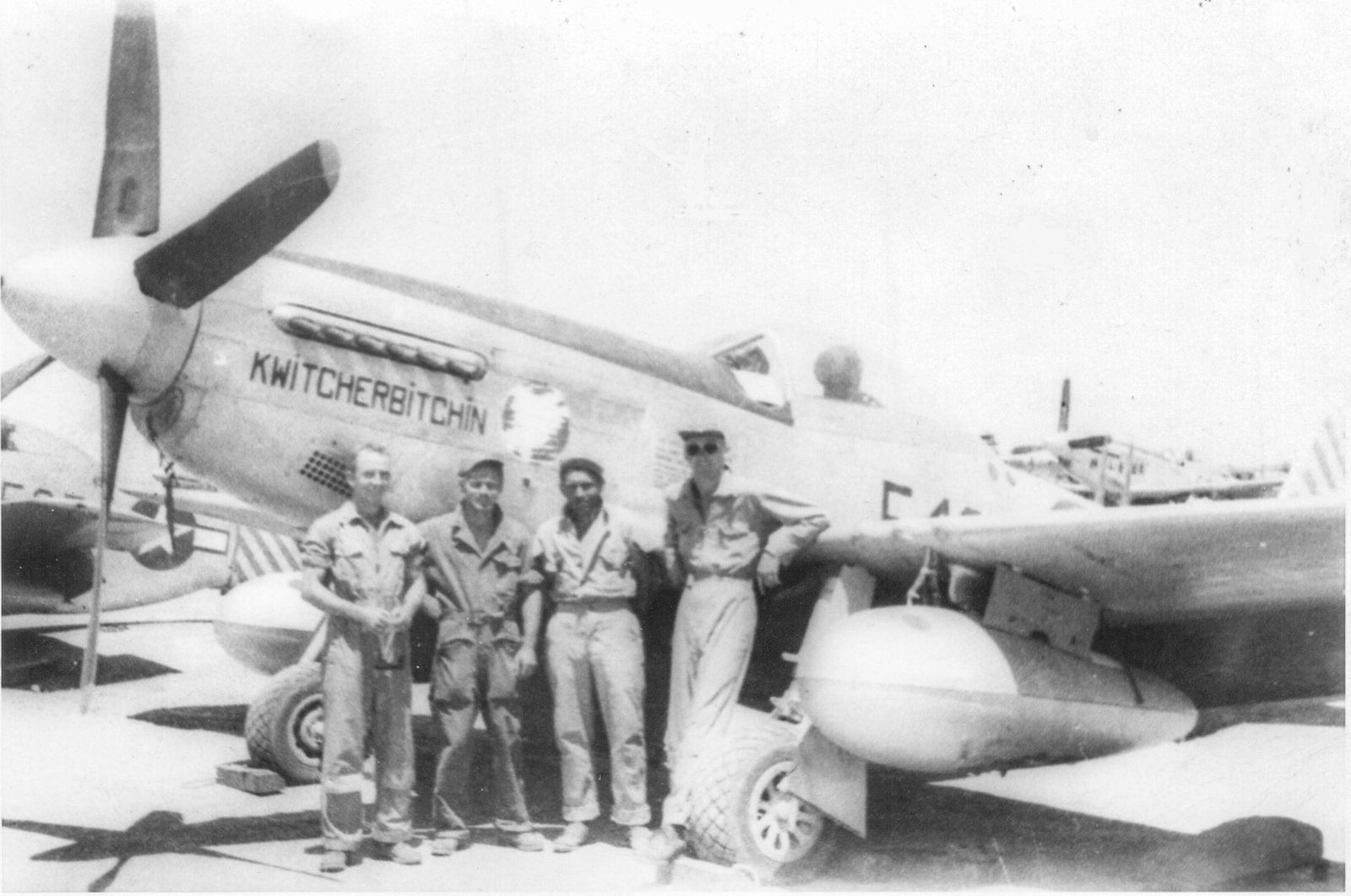

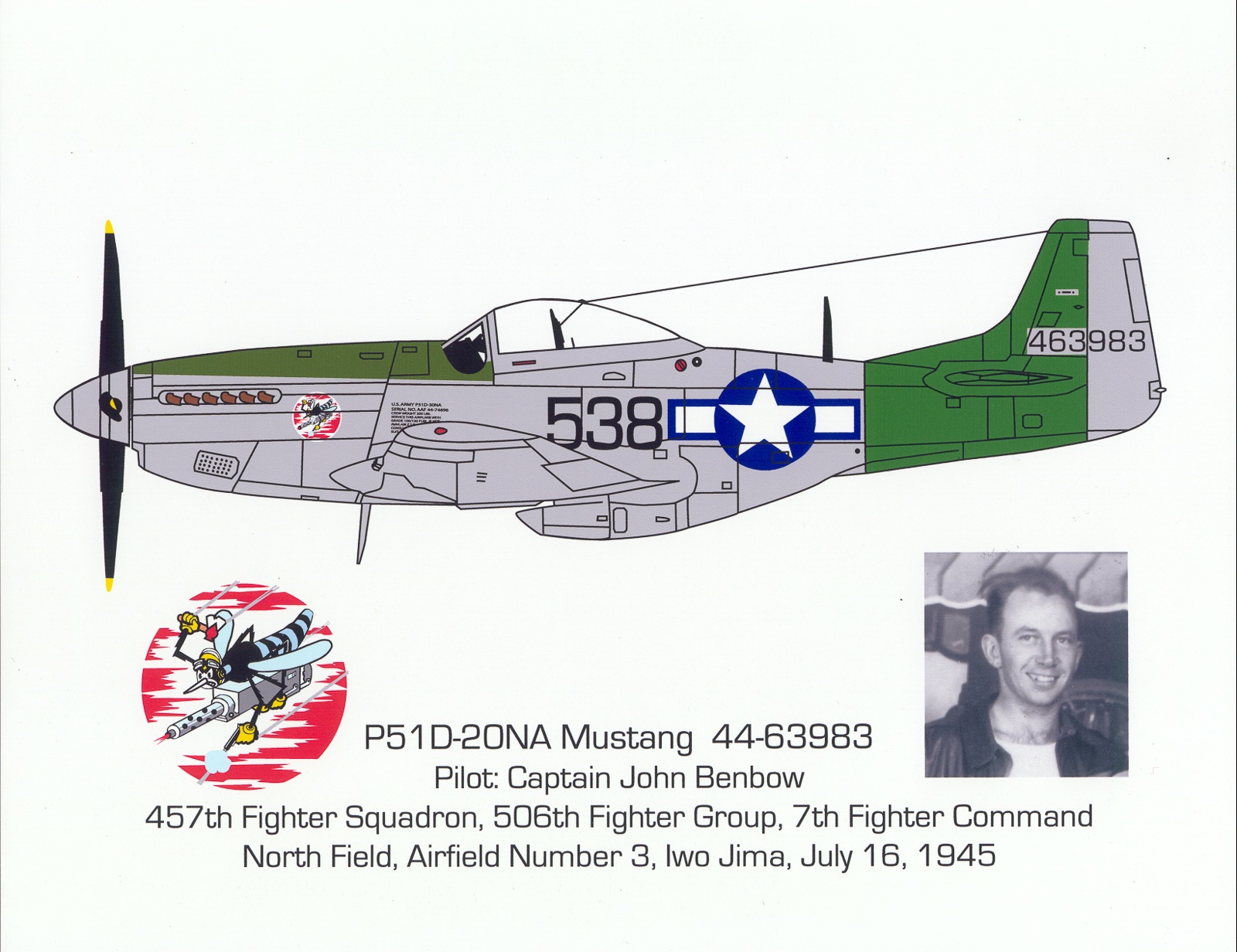

Capt. Bill Lawrence was leading Green Flight in what is arguably the group’s most famous Mustang, P-51D #44-72853 (#540), nicknamed KWITCHERBITCHIN. Although there are no documents to support it, Ralph Gardner told Benbow’s nephew a number of times that his uncle was Lawrence’s wingman that day. Benbow was flying as Green 3 in #44-63983 (#538) with 2nd Lieutenant (Lt) Joseph Winn on his wing. At 1335hrs, the group was at 15,000 feet when they made landfall near Shima and turned north to fly up the west side of Ise Bay towards Suzuka. In an area between Akenogahara and Tse, the group ran into a huge dogfight between 30+ Mustangs from the 21st FG and approximately sixty, single-engined Japanese fighters identified as Franks, Georges, Tonys, and Zeros. The largest dogfight in the 506th’s history was on, and it lasted over 30 minutes in airspace approximately 50 miles long and 20 miles wide between Akenogahara in the south and Nagoya in the north.

The Mission Report detailed what happened when Green Flight encountered a Japanese fighter, “Capt. Lawrence opened fire when in range and followed it down through a dive, a roll and split-ess [sic]. The Jap smoked and large pieces commenced to fall off the enemy plane. Captain Benbow, Green #3, called Capt. Lawrence, saying, ‘That’s enough Bill, you’ve got him.’ Lt Winn, Green #4, by this time was flying through so much debris he was forced to pull off temporarily losing his leader, Capt. Benbow. Capt. Benbow was not seen again. About the same time and in the same general area what was believed to be a P-51 was observed by another flight apparently in trouble…this aircraft disappeared into the clouds at about 8000ft. The time was reported 1350. It is possible that Capt. Benbow’s plane was damaged by pieces of the A/C shot down by Capt. Lawrence.” In his Encounter Report, Lawrence wrote, “I pulled up to assemble the flight but Captain Benbow did not rejoin. Prior to Captain Benbow’s disappearance, his radio reception and transmission was excellent and he had not reported any mechanical trouble whatsoever.”

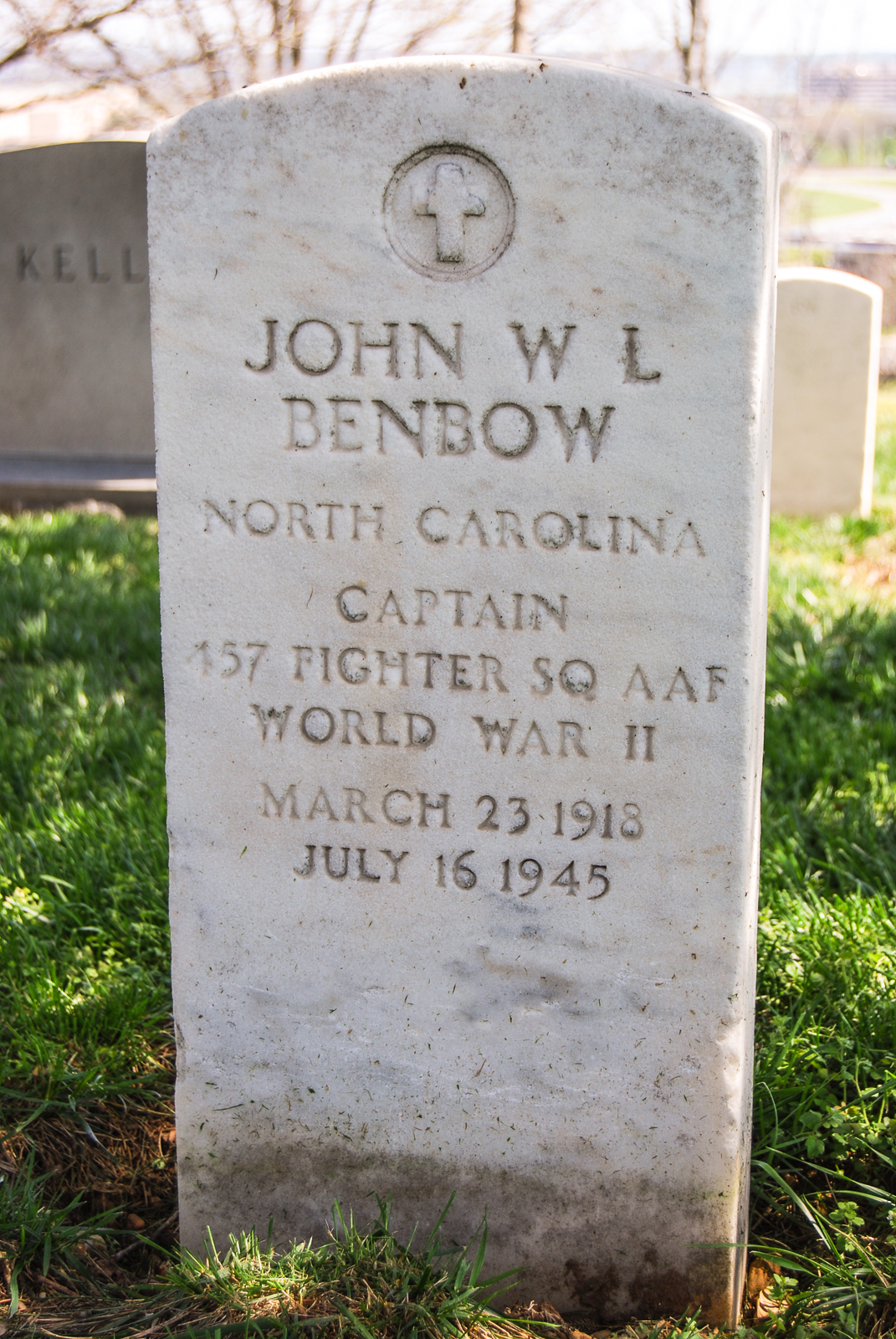

John’s Mustang crashed in a wooded area approximately 15 miles west of Nagoya. Local villagers removed Benbow’s body from the wreckage and buried him next to his aircraft. In April 1946, a Graves Recovery Team exhumed John’s body and buried him in the United States Armed Forces Cemetery Yokohama #1 on the island of Honshu, Japan. At the wishes of his family, Capt. Benbow was disinterred and brought home to the United States and buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery on January 17th, 1949.

What brought down Benbow’s P-51 and why he didn’t bail out of his stricken fighter remain a mystery to this day. There have been claims that he was shot down by a Ki-100 flown by Japanese Ace Maj Yohei Hinoki, but Benbow’s nephew believes, as others do, that some of the debris from Bill Lawrence’s victim damaged John’s Mustang. Whatever the cause, on that day America lost a courageous fighter pilot, one who Maj. Malcolm Watters once described as “a good pilot and a very good man,” Bill Lawrence lost a friend, and the Benbow family lost a loving husband, brother, and son.

Be the first to comment

Graphic Design, Branding and Aviation Art