by Moreno Aguiari

One of the most powerful aspects of studying World War II is the virtually unending supply of stories involving heroism, self-sacrifice and duty. Today we recount one of these tales which almost feels too incredible for reality, but as the saying goes, truth is often stranger than fiction. The setting for our story is the picturesque island of Sardinia, in the Tyrrhenian Sea just 300 or so miles southwest of Rome on the Italian mainland. It is August, 1943, just a few weeks shy of the Armistice of Cassibille, where Italy formally surrendered to the Allies. Italians were in their third year of conflict and all too aware of the likely outcome – it was just a matter of when. Indeed, the Italian Armed Forces were in a critical state, with their air force, the Regia Aeronautica, nearing collapse. At this point in the war, few serviceable combat aircraft were available, or qualified flight crews capable of flying them, but perhaps most importantly, the fuel supply was virtually exhausted. In Sardinia, given its isolation from mainland Italy, the crisis was even more precarious.

At the beginning of August 1943, the Regia Aeronautica transferred three Macchi MC.205 Veltro fighters from 310° Gruppo (310th Squadron), along with four pilots and nine airmen to Decimomannu airport, near Cagliari, Sardinia. Here they were to conduct strategic photographic missions over Tunisia, Algeria, the Sicilian Channel, and Malta. Technicians had already modified each of these fighters with camera equipment to fulfill their reconnaissance role. The legendary double ace, Capitano (Capt) Adriano Visconti, was the man in charge of 310° Gruppo. He was perhaps the most famous Italian pilot in World War II. Visconti brought fellow pilots Sottotenente (2d Lt) Sajeva, Marshal Magnaghi and Sergente (Sgt) Laiolo with him. With three pilots, two per shift with one in reserve, the Veltros carried out daily reconnaissance missions over the ports and airfields of Bone, Philippeville, Bougie, Bizerte, the Isle of Dogs, La Calle, and Kairouan (on Sicily) with its group of airfields. Upon returning to Decimomannu, a Macchi MC.202 fighter would transport the freshly-exposed, reconnaissance film to Guidonia airport, near Rome, for development and analysis.

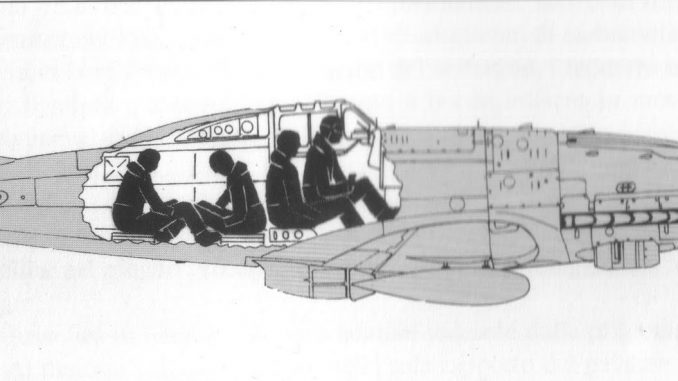

On September 7th, 1943, Visconti made a reconnaissance flight over the port of Bizerte in Tunisia. The following day, Sottotenente Sajeva flew an uneventful mission over Tunis. But that same evening, 310° Gruppo received the news of the armistice. The Armistice of Cassibile, as it became known, was signed in secret in Cassibile, Sicily on September 3rd, 1943. U.S. Army General Walter Bedell Smith, representing the Allies, and Brigadier General Giuseppe Castellano, signing for the Kingdom of Italy, were the two men responsible for concluding this momentous occasion. The news became public on September 8th, and caught everyone at Decimomannu by surprise. Unprepared, and confused about what should come next, the officers of 310° Gruppo tried to communicate with headquarters on the Italian mainland. They were unsuccessful in this endeavor, so Adriano Visconti gathered his men and they decided to return to Guidonia, on the outskirts of Rome, to save their aircraft and await future orders. However, Visconti and his men faced a major problem; with just three single-seat fighters, how could they move all 12 men in the reconnaissance flight off the island of Sardinia. They discussed the problem in depth, but some of them remembered how others had escaped from Tunisia during a previous surrender in North Africa earlier in the war. On that occasion, pilots had ferried some of their airmen to safety by having them sit on their laps during the flight from Tunisia to Sicily. Using this idea, an armorer proposed removing the bulky photographic apparatus and heavy armor in order to reduce weight and make room so that two men could huddle together in the aft fuselage, facing each other on a small custom-built bench. He also suggested removing the pilot’s seat and discarding his parachute. This configuration would then allow for two men in the fuselage behind the pilot, while another sat on his lap. It was a crazy idea, but it just might work!

Once Visconti signed off on the idea, the armorers modified the three aircraft in just a few hours. There was much apprehension before the flight, because it wasn’t clear at this point exactly what the Allied and German intentions entailed. Would the fighting simply stop, with the Germans withdrawing from Italy? While this might have seemed unlikely, no one really knew at the time.

Visconti’s men had stripped their Veltros of everything unnecessary to reduce weight, including life rafts, so the team planned to fly over land for as much of the route as Italy’s geography allowed. They would fly at low altitude, no more than 3,000 feet, to ensure their passengers had enough oxygen in the free air. The route they selected headed first towards Milis, then via Olbia, Bastia (Corsica), Elba Island, Civitavecchia and Rome to Guidonia. They chose Milis, because it was another Sardinian airfield just 60 miles or so north of Decimomannu, and home to the fighters of 51º Stormo (Wing). Visconti hoped they could link up with 51º Stormo, and that the two units could then fly together for the mainland.

At first light on the morning of September 9th, eleven men took up their positions inside the three fighters, and prepared for takeoff (one of their number, an intelligence officer, had opted to his own way home). The skies were partially clear and calm, so Visconti ordered his men to take off. Luckily, Decimomannu had a lengthy runway, and the overweight, tail-heavy Veltros needed every scrap of tarmac as they reluctantly clawed their way into the sky. As planned, the formation headed first for Milis, but all seemed quiet with 51º Stormo’s MC.205s down below, so they ditched the idea of forming up with them, and headed onwards to Olbia, then Bastia in Corsica, Elba Island, Civitavecchia, and Rome. After roughly two and a half hours of incredible discomfort in their cramped aircraft, the pilots finally arrived over Guidonia.

Adriano Visconti was the first to line up his Veltro for landing, but he very quickly realized his airspeed was far too high, so he chose to go around flying very close to the airfield’s hangars in the process. Sajeva was next make his landing attempt. His airspeed was also too high, but he landed regardless and managed to stop just before runway’s end. Laiolo, followed, touching down almost too short, and narrowly avoiding the small cones marking the runway threshold. Fortunately, his landing continued without further issue.

Visconti came around for his second landing attempt, although his airspeed was too high yet again. However, given the successful examples offered by his fellow pilots, he elected to put his airplane down anyway, using every inch of runway and then some. He ended up rolling out between two rows of parked airplanes and finally ground-looped his Veltro sharply left, not coming to a halt until he was actually inside a hangar! Thankfully it was empty at the time. One-by-one the 11 men unfolded themselves from their cramped positions, spilling stiffly out of their aircraft to the consternation of the many who witnessed the event.

In the following days, moments of absolute confusion, Visconti made the fateful decision to fly with the RSI (the Repubblica Sociale Italiana), maintaining faith with his original military oath of allegiance. They assigned him to 1° Gruppo Caccia, again equipped with the Macchi MC.205. This choice was clear evidence of Visconti’s character and patriotic spirit, as he was not particularly pro-German. Ample proof for this fact is evident in that Visconti himself demanded the overpainting of the Germanic crosses, then on the RSI’s fighters, with the Italian national insignia, albeit a slightly different version of it to those used in the early war years. Visconti soon took command of 1a Squadriglia and began flying the Veltro on desperate missions to counter American bombing raids, engaging in furious combat with their P-38 and P-47 escorts. On January 3rd, 1944, Visconti shot down a P-38 Lightning his first victim while serving with the RSI. He claimed three further victories in the following months, and rose to command 1° Gruppo Caccia, before being posted to Germany for conversion onto the Messerschmitt BF-109G-6, the aircraft in he would fly for the remainder of the war, prior to his tragic epilogue which Luigino Caliaro covered in a story HERE.

Moreno Aguiari wishes to offer many thanks for support in writing this article to Gregory Alegi, writer and aviation historian. For more information about Gregory’s work, visit www.gregoryalegi.com. Furthermore, for those who can read Italian, Visconti’s story is covered in depth within Giovanni Massimello’s fascinating book Adriano Visconti – L’Aviatore di Tripoli which is available for sale HERE.

Be the first to comment

Graphic Design, Branding and Aviation Art