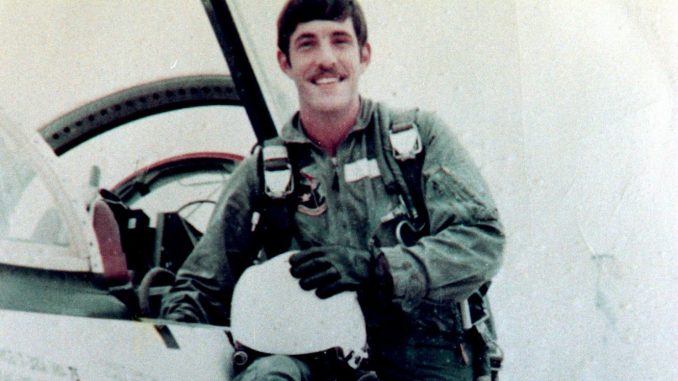

Mike was a spitting image of what most people believe a young Air Force officer should look like: tall, handsome, with a hospitable grin and approachable demeanor. A 1970 graduate of the Air Force Academy, he lettered on varsity tennis and soccer teams. In 1968 and 1968, Mike was nominated to the All-Rocky Mountain League Soccer Team. He studied psychology and in 1971 received his aeronautical rating after graduation from the Academy. After qualifying on A-37B Dragonfly (Super Tweet) Cessna attack aircraft, he was deployed to Vietnam to serve with the 8th Special Operations Squadron.

The 8th Special Operations Squadron is one of the oldest units in the United States Air Force, organized in 1917 at Camp Kelly, Texas. The unit fought on the Western Front in World War I, then called The Great War, and primarily flew the Dayton-Wright DH-4, a reconnaissance aircraft. The squadron fought and flew in the Pacific during World War II and served in Korea flying Douglas B-26 Invaders. During the Vietnam War, the unit flew the Martin B-57 Canberra medium bomber and in the closing years of the conflict changed over to the small but lethal Cessna A-37 Dragonfly, a light attack aircraft.

When Mike saddled-up to an A-37B Dragonfly at the Bien Hoa Airbase in Vietnam, he did so as a member of an air commando unit, which suggests to this old Intelligence guessaholic that he was flying covert missions into Laos and Cambodia. He also flew COIN (counter-insurgency) missions and served as a forward air controller. On May 11, 1972, while starting a bombing run on enemy artillery positions on the outskirts of An Loc near the Cambodian border, fellow airmen saw tracer rounds from ground fire coming up toward Mike’s A-37B. The anti-aircraft rounds found their mark.

Major James Connally, his flight commander, described the tragic incident in a letter to Mike’s parents, “Mike’s plane was hit and began streaming fuel. He must have been killed instantly since he did not transmit a distress call of any kind. The aircraft flew a short distance on its own and then slowly rolled over, exploding on impact in enemy-held territory.” Yet the fog of war relates another version, of how the Dragonfly had inverted (flying upside down) and that Mike ejected from the stricken aircraft. Nevertheless, flying a low altitude to drop napalm, doing so would have propelled him into the ground.

Whatever the case, other aircraft were dispatched to the area to provide cover for an Army chopper rescue team, all for naught. The enemy threw up what was described as a ‘murderous hail of fire’ which forced a cancelation of the recovery and/or rescue attempt. Mike had become another cold statistic of war, an MIA (Missing in Action). The following day an Air Force chaplain visited the home of Mike’s parents in St. Louis to inform them their son had been killed in action, but his remains could not be recovered since he went down in enemy-held territory. That tragic explanation would be the same story Mike’s grieving parents would hear for the next 26 years, a story that soon bore little truth.

About six months after the incident, a South Vietnamese Army patrol located the crash site. In close proximity the patrol recovered six bone fragments, a Beacon radio, two compasses, an American flag, a parachute, remnants of a pistol holder, a one-man life raft, dog tags, fragments of a flight suit, a wallet with family pictures and an I.D. with the wording: 1st Lt. Blassie, Michael Joseph.

With the discovery of the crash site and personal effects, thus began a sequence of events that literally baffles the imagination. On November 2, 1972, Michael Blassie’s remains were turned over to the mortuary in Saigon. As his I.D. indicated, Michael was 6’ in height and weighed 200 lbs. By testing bone fragments using a controversial technique known as ‘morphological approximation’, the estimated age of the deceased was between 26 to 33 years. Mike was 24 years old at the time of his death, ‘outside’ of the so-called age bracket. The height of the deceased was estimated to be between 65.2 inches and 71.5 inches. Mike stood at 72 inches. By using a single strand of hair found in the flight suit, tests indicated the decease’s blood type was not type “A”, the blood type recorded as Blassie’s. Ignoring official chain-of-custody documents, the remains (bones) were reclassified and designated to be ‘unknown.’

DNA testing was in its infancy at the time of Mike’s death and the procedures of remains identification sometimes seemed like guesswork. Incredibly, changing lab reports and closing cases, basically ‘getting the job done’ due to internal pressures, was not uncommon at the time. The methods were ‘completely worthless’ according to many forensic experts and to estimate a victim’s height by the ‘morphological’ method was later deemed ‘impossible’.

Disputes over lab details on a plane shot down over Laos finally sparked an independent report commissioned by the Army. The findings: ‘Morphological approximation’ was ‘not a logical nor correct technique.’ The procedure was discontinued. The horror behind the findings meant the probability existed that undetermined numbers of American war dead may have been buried in the wrong graves. And as if adding salt to emotional wounds, the Blassie family in St. Louis was never told that Michael’s aircraft had been found nor that his remains had been recovered. The ‘unknown’ remains were stored in the Army’s Central Identification Laboratory under the file number X-26.

Congress passed a law in 1973 authorizing the Defense Department to bury a Vietnam Unknown at Arlington National Cemetery. Although a gravesite was prepared, it remained empty for eleven years. Under pressure from the Veterans of Foreign Wars and the American Legion, the Congress and the Reagan Administration collectively agreed to go ahead with a burial. The year was 1984, an election year.

The Secretary of the Army wanted the ceremony to take place on Veterans Day, November 11. However, as the political animals in Washington, DC always do, that date would be five days after the election and the political elite did not want to miss a public relations opportunity. The date for the interment was pushed back to May 28, 1984: Memorial Day. One set of remains was available: X-26.

At the time, Major Johnie Webb was in charge of the Central Identification Laboratory and was acquainted with the Blassie case. He also understood Washington politics. Presented with papers to sign confirming the X-26 remains would never be identified, Webb refused to sign. Even the senior anthropologist who developed the ‘morphological approximation’ technique, a man named Furue, sided with Webb to adamantly oppose the burial at Arlington. Major Webb was given six months by the Pentagon to identify the remains of X-26. If a positive I.D. was not made by the end of six months, Webb was ordered to sign the certification. On March 21, 1984, Webb reluctantly signed.

Then, according to Webb, he was ordered by Army HQ in the Pentagon to destroy any evidence linking Blassie to file X-26, including the personal artifacts from the crash site. Webb wrestled with mixed emotions, of doing the right thing versus following orders. It was ‘the struggle of my life’, according to Webb. Major Webb chose to do what he considered to be the proper course of action: he disobeyed orders, putting his military career in jeopardy plus running the risk of a court-martial, and hid Blassie’s remains and crash-site artifacts where no one would ever find them…in the casket with X-26.

On May 28, 1984, a Third Army Old Guard horse-drawn caisson bearing the remains of X-26 moved slowly along Constitution Avenue. Over a quarter million people lined the route to Arlington National Cemetery, a series of 21-gun salutes cracked sharply in the distance, and military bands played respectful music. Approximately 100 vets of the Vietnam War, some bearded, some pushing their brothers in wheelchairs, some wearing jungle hats and worn-out camouflaged fatigues, followed the parade.

A few remarks of President Ronald Reagan’s emotional farewell: “Today, we pause to embrace him and all who served so well in a war whose end offered no parades, no flags, and so little thanks. We write no last chapters. We close no books. We put away no final memories.” Placing a Medal of Honor on X-26’s flag-draped casket, President Reagan concluded, “Thank you, dear son, and may God cradle you in his loving arms.”

The Blassie family was not in attendance. They had no way of knowing the remains of X-26 were that of a son and brother, their loved one who was killed in action in Vietnam. They didn’t even know Michael’s aircraft had been found, his remains recovered, as were artifacts to prove the deceased flyboy was actually Michael Joseph Blassie.

Michael’s younger sister, Patricia Blassie, was 13 years old when her brother, the oldest of five siblings, was listed as ‘MIA, presumed dead’ in Vietnam. She recalled, “My father served in Normandy during World War II and he never got over losing Michael. He and Michael were very close. Dad set up a little memorial in the basement and would go down there all the time and just sit.”

Patricia Blassie joined the Air Force as an enlisted airman, she now holds the rank of Lt. Colonel. Next, in Part II of ‘Coming Home’ she relates the Blassie family story, of the heartbreak, all the unanswered questions, and the final fight to have Michael ‘returned home.’

Click HERE for part II

Pete Mecca is a Vietnam veteran. For story consideration visit his website at VETERANSARTICLE.COM and click on “contact us.”

Be the first to comment

Graphic Design, Branding and Aviation Art