WarbirdsNews is always on the look out for interesting stories of personal experiences in flight, whether they are historical or contemporary. We recently caught up with well-known warbird pilot and former naval aviator, Doug Matthews, and he sent us a fascinating piece he wrote describing what it’s like to fly the F-86 Sabre. Matthews regularly performs in his F-86 on the air show circuit these days, but what was it like for him to strap on the potent Korean War fighter for the first time? Read on and you will find out….

——————————

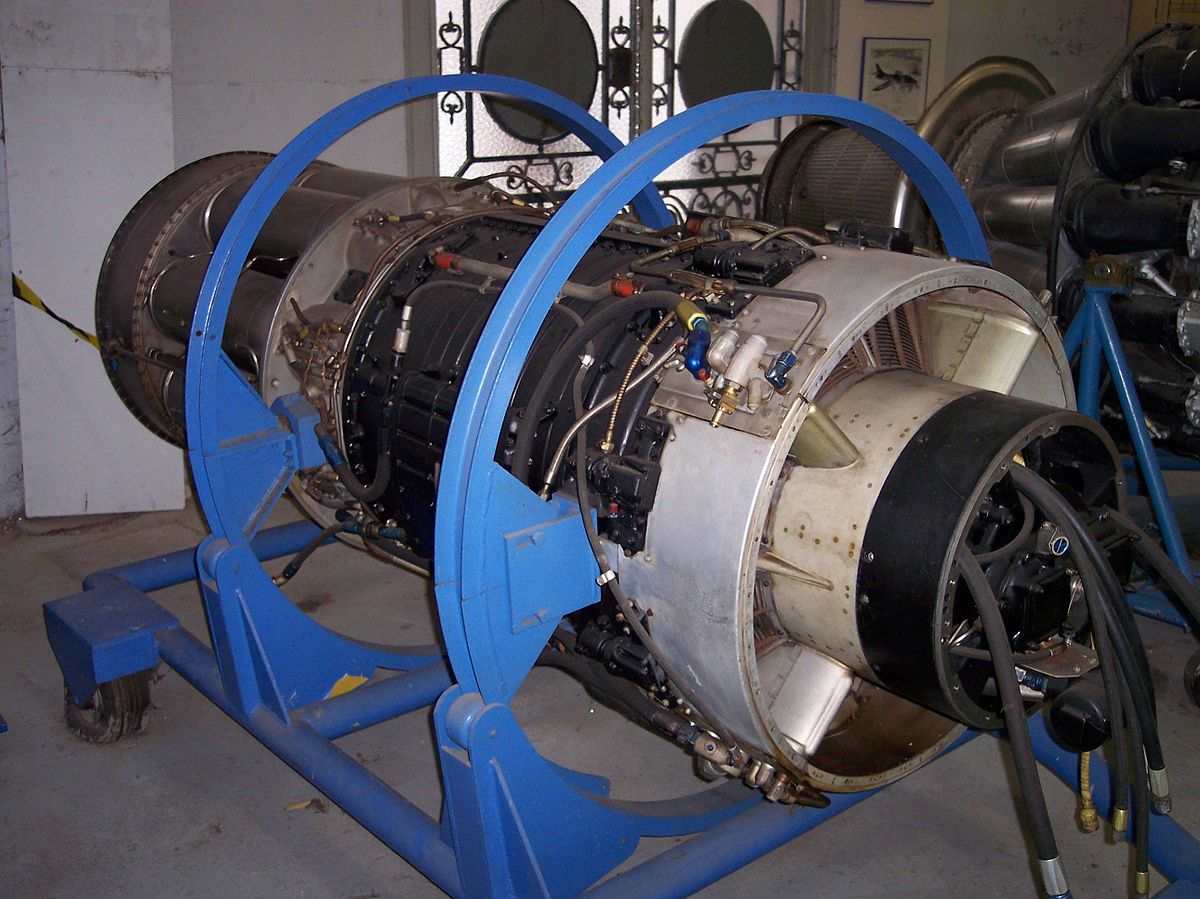

Over 7,800 F-86 Sabre jets were made between 1949 and 1956 in the U.S., Japan and Italy. Canada and Australia built an additional 1,927 of the popular airplane for a total of almost 10,000 Sabres. The F-86 was operated by the U.S. Air Force and Navy as well as many foreign allies (as late as 1994!). It was the first supersonic-capable jet (1947). Its typical weapons were six .50 caliber machine guns although later versions had cannon and missiles. 90 survive today, 9 which are flying; Built by North American Aviation, the first model was delivered to the USAF in 1948. The engine is a General Electric J-47.

As America’s first swept-wing fighter, the F-86 Sabre was very successful in the Korean war against the MiG 15 and ultimately achieved a 10-to-1 kill ratio. However, in the early days of the war, the situation was very different. U.S. pilots had no prior experience fighting against jets with the MiG 15’s capabilities, so tactics naturally had to evolve in a hurry. At the outbreak of war, our primary fighter was the F-80 Shooting Star, a WWII-era design. The F-80 was a measured combat success, but no match for the MiG 15. As F-86’s started to arrive in theatre, the balance in the air war improved for the Allies, but it was soon clear that “their swept wing fighter” was in many ways as good, or better than “our swept wing fighter”!

A quick visual inspection of the MiG 15 is enough to give a knowledgeable viewer distinct opinions. It looks stubby and has a big, fat-planform wing. It has a jet engine closely derived from the Rolls-Royce Nene, a mis-guided “gift” of the British government to the Soviets in the late 40s. (Interestingly, the U.S. also developed jet engines from similar British designs for naval fighters like the F9F Panther.) It also has machine cannon as armament. Put these initial factors together and you get a very fast jet with a service ceiling higher than an F-86, an aircraft with a good climb and turn rate and an impressive weapons platform. Added to this was the fact that in addition to the North Korean fighter pilots, many of those flying the MiG 15 against Western forces were actually battle-proven Chinese and Russian aircrew!

The first Sabre variant, the F-86A, was a great step forward from the F-80, but it still lacked the design attributes needed to overcome all of the MiG 15’s advantages. As hard-won pilot feedback arrived at North American and the USAF, the design evolved eventually into the F-86F; which included a wing shape modification, leading edge slats and a better version of the General Electric J-47 engine (-27). These improvements, coupled with a U.S. pilot’s training and discipline, lead to an impressive score of victories over the MiG 15 as the Korean War progressed.

Over the years, I have had the opportunity to fly two Canadian Sabre variants; the Mk.5 and Mk.6. Now, more than sixty years after Korea, I recently renewed my acquaintance with this magnificent bird. My 20-year hiatus with the F-86 coupled with flying so many other fighters during the interim, left me feeling like I was starting all over again. After careful study of the manuals and pilot reports, I went through a detailed pre-flight with my maintenance technician on the day of my flight. Prior to mount up, important things to remember are:

- There is only one engine.

- The cockpit layout is not, how shall we say, “ergonometrically balanced”. As with many 1940’s vintage aircraft, the instruments are poorly located. Flying in solid IMC weather will require a third eyeball. And prayer. Switches and lights are seemingly placed at random throughout the compact cockpit.

- Flight controls are hydraulically boosted, either by the engine pump or an emergency pump. Without hydraulic pressure from one of those sources, the aircraft is uncontrollable, necessitating an immediate “evacuation”. The ejection seat is first generation (ballistic), which is Latin for either “makes men shorter” or “bad back waiting”.

- Oh, and yes… there is only one engine.

- The leading edge slats are aerodynamic/mechanical. This means that they extend and retract as they sense the wing’s angle of attack. Hopefully, they will all operate simultaneously.

- There are NO position indicators for the flaps, slats, trim tabs or speed-brakes.

- As an early, axial-flow jet engine, the fuel control is very basic. Therefore starting the engine is a tedious business, requiring careful orchestration of the throttle and EGT.

- Avionics in this F-86 are “authentic” (mostly 1950’s vintage), with the cockpit having very little room for a 6’2” pilot, much less one looking for a place to mount an iPad.

- Internal fuel capacity is way less than I would like, even for a “fam-hop”. An average flight (takeoff, climb to FL350, cruise for an hour and land, yields an average fuel flow of 300 gph. But on takeoff, the fuel flow is closer to 800 gph. My flight will be a takeoff, climb to 10,000 for air-work (slow flight and stall series), then descend for three landing circuits. There is no chart to plan this sort of flight so I do some estimates based on the T-33/F-80 I have been flying. Full internal is around 2800 pounds of Jet A and I should taxi in with 1000 pounds. There are two long runways and the weather meets my personal minimums for such flights…..CAVU.

As I entered the cockpit, I remembered how cramped it was, especially for a tall pilot. There was also that familiar musty smell that seems to lurk in all old military cockpits. Strapping in was difficult due to tight quarters, even though the crew chief helped. I looked over the instrument panel in denial…gosh it was “authentic” (i.e. antiquated).

After start, I ran through an extensive “ballet” of after-start system checks with my ground support crew. These checks verify the pitch-trim setting for takeoff (remember-no indicators, just a light) and adjustability, flight controls, back-up flight control systems, etc. Of course, the whole time I am sitting there doing these checks with the engine running, I was constantly thinking “fuel burn”!

I taxied out with little power and was immediately reminded of the poor nose-wheel steering system. Taxi and Before Takeoff checks were completed and I took to the runway for the “Line Up” items. I told the tower that I needed a few minutes on the runway and I did my Emergency Fuel Control check….twice! I powered up and started the roll briskly. Accelerating to rotation speed, I pulled back the appropriate amount. The bird hesitated, then lifted off nicely. Accelerating quickly to 180 kts., I retracted the landing gear and flaps.

I cleared the airport area and climbed up for the air work. I was reminded of what a sweet plane it is. The plane is so aerodynamically clean, even with drop tanks, that I was at 250 kts. before I knew it! The throttle needed retarding to half! Air-work went well and renewed my memory of the tremendous flight control response. The roll rate is awesome! I included some work with the speed brakes, changing configuration several times. Once again comfortable, I returned for the airport work. I entered the pattern from a 360 overhead at 200 kts., the airport speed limit! Out went the speed brakes, then the landing gear and full flaps. As the plane approaches 160 kts., I was ready for pattern work. As clean and light as the plane was, it was a challenge to slow to the desired 120 kts. on short final. By the fourth landing, I was crossing the numbers just above 100 kts., my short runway target speed. But I had this feeling of sitting too low in the cockpit, with limited forward vision on landings. The seat is not height-adjustable once you are seated, so I would need to find the right spot for future flights.

On flight #2, I will work on my air show aerobatic routine and simulated engine-out profiles. We will also run some tests and calculations on taking off with half flaps. It is very unusual to make a full-flap takeoff in a jet so we will see how it goes in a series of half-flap launches and re-plot our takeoff charts. Later, maybe I will re-create a Korean war “return to base with critical fuel” profile like they did “back in the day”-climb to 35,000+ feet, SHUT OFF a perfectly good engine, glide all the way to home base, then light her up for the landing! Then again, maybe I’ll just pretend to and say I did!

I think about how it must have been to fly the machine in wartime-Korea and against the MiG 15. On the plus-side; I could out-accelerate a MiG, I have a reliable and advanced machine, plus a lead-computing gun-sight. I have six .50 cal. machine guns. I’m trained well, and we have great flight discipline. We learn the MiG’s advantages and employ our tactics accordingly. The negatives; at the start of a fight, we both release our drop tanks. Our wing loading is similar, but he has a much better thrust to weight ratio, so he may be able to out climb me (rate-wise). The MiG can out-turn me, also has a 5000’ service ceiling advantage (50,000’) and likes to come down at us screaming fast! He has a CANNON to shoot at me! We have to fly 250+ miles to reach the battle zone, whereas he fights over home turf.

Given the choice of aircraft, I would still take the F-86F over a MiG. By 1952 standards, the Sabre is a sleek, modern war machine… a state-of-the-art weapons system. The MiG on the other hand seems bulky, unattractive, out of balance aesthetically, crudely manufactured, frailly-powered and, well…… Russian! But the MiG 15 is no slouch, and if flown by a real fighter pilot, it is a formidable adversary. It is a great performer and if in battle, I would take extreme satisfaction in every one I could shoot down!

——————————————-

WarbirdsNews hopes you have enjoyed reading Doug Matthew’s tale of Sabre-flying, and wishes to thank him very much for submitting it to us for publication. Be sure to see him fly if you get the chance, and to check out his air show company, Classic Fighters Airshows, to see which shows his aircraft will be attending.

Nice!

Did you know my husband Walter g Zisette. He flew f 86 fighters from 1951 to 1953. Stationed in Las Vegas before being sent todo Korean. Shot down 3 mins. And was given a medal for going beyond the call of duty. I would love to talk to anyone who served with him. Thank you. June Zisette. Gig harbor wa. 98332