(Image Credit: Smithsonian Institution)

During World War II more than 100,000 Long Islanders were taking home paychecks from aviation-related businesses. Grumman Aircraft, a longtime linchpin of the Long Island economy is probably the best known of the aerospace entities that made their home there, and at one time it was the largest employer on the island, employing over 25,000 people and occupying six million square feet of building space where their products were designed, tested and built. Other notable aircraft manufacturers based on Long Island were Republic Aviation and Fairchild Aircraft who while perhaps not as large a Grumman, produced some legendary machines in their own right.

The end of the cold war caused defense budgets to shrink, forcing massive consolidation in the aerospace industry. Grumman and Northrup merged and most the of their manufacturing facilities on the island were shuttered. Republic and Fairchild merged and subsequently consolidated and reconsolidated with various other entities and are now part of a San Antonio-based division of the Israeli defense contractor, Elbit Systems.

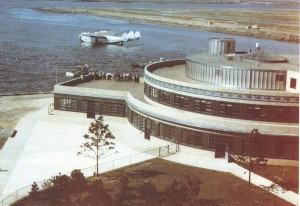

(Image Credit: Everything PanAm)

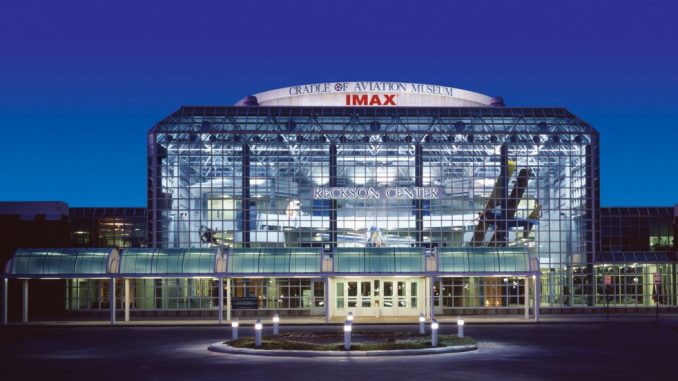

It’s against this historical backdrop that the Cradle of Aviation Museum was founded. The museum’s first acquisition in the seventies was a World War I Curtiss JN-4D “Jenny,” discovered in an Iowa pig barn that was the first plane owned by Charles Lindbergh in his barnstorming days. The museum first opened in 1980 with a few planes housed in a couple of unrestored hangars on the closed Mitchell Field Air Force Base, but after years and years of dedicated work and significant fundraising efforts, the modern facility within it now resides was built, opening its doors to the public in 2002.

(Image Credit: Michael Grey– CC 2.0)

(Image Credit: Ad Meskins/ CC 3.0)

the 1918 Breese Penguin.

(Image Credit: Ad Meskins/ CC 3.0)

(Image Credit: Ad Meskins/ CC 3.0)

(Image Credit: Michael Grey– CC 2.0)

(Image Credit: Michael Grey– CC 2.0)

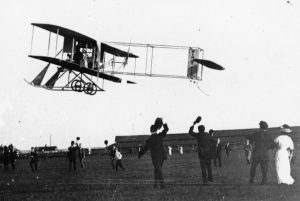

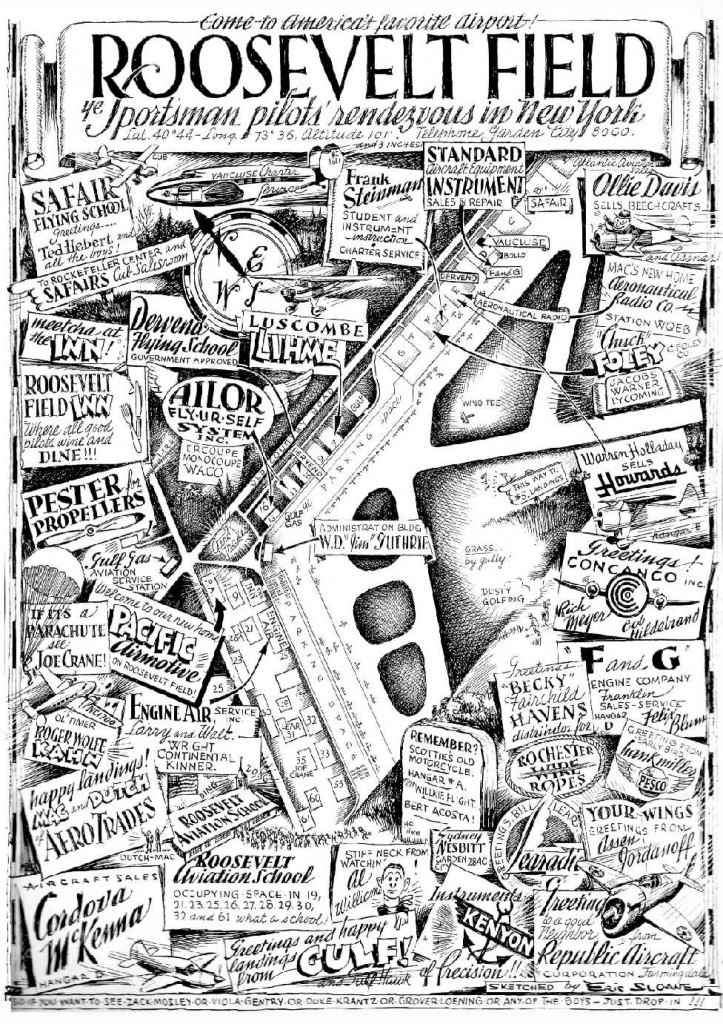

The exhibits at the museum are separated into eight galleries that chronologically document the history of manned flight from experiments with kites, gliders and hot air balloon to the exploration of space, with the vast majority of the craft on display being from the Island. Some of the memorable exhibits from the earliest days of aviation are exacting replicas of the Wright EX “Vin Fiz Flyer”, the Herring-Curtiss No. 1 Golden Flyer, a Sperry Messenger and a 1918 Curtiss/Sperry Aerial Torpedo, a world war one flying bomb which was called an aerial torpedo in vintage parlance.

There is a Bleriot Type XI, and the sole surviving example of the aptly-named 1918 Breese Penguin, a World War One-era non-flying flight trainer with wings were too short and an engine too small to allow it to fly. These trainer “aircraft” were intended to be just as unmanageable as the real aircraft of the day and thus had no brakes or steerable wheels which made them quite difficult to control, but as they never left the ground there was some degree of safety built into the design. Another sole survivor of its type on display from this era is the museum’s Aircraft Engineering Corporation “Ace” biplane which was the first American civil aircraft to be produced following World War One. A fully aerobatic and relatively inexpensive plane, the Ace failed in the marketplace due to competition from the flood of WWI surplus planes being sold to civil aviation on the cheap at war’s end.

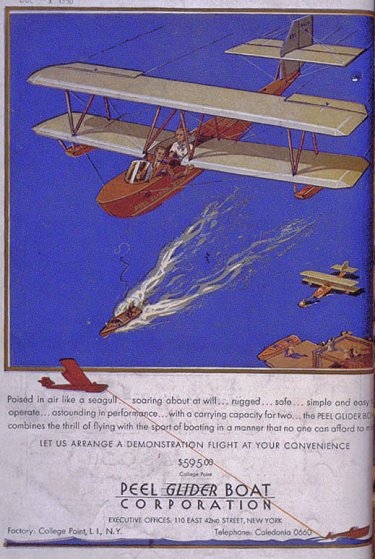

The museum also has one of only two remaining examples of the Ryan Brougham, built along identical lines Ryan’s NYP “Spirit of St.Louis” in an attempt to cash in on the famous plane’s cachet. The Brougham on display has been modified to reproduce the appearance of its more famous relative which currently resides in the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. Also on display from the interwar era are a 1929 Brunner-Winkle Bird and a Peel Z-1 Glider Boat, meant to towed behind a motor boat to give the then flight-obsessed public a relatively inexpensive way to experience flying a plane.

The shadow of Grumman looms large over Long Island’s aviation history, many of the museum’s volunteers are ex-Grumman employees and significant monetary support of the facility has been provided by Grumman family, so it’s not surprising that there is an extensive collection of Grumman aircraft with their feline nomenclature in evidence, including a Grumman F3F-2 reproduction, a G-21 Goose, TBM-3E Avenger, an F4F-3 Wildcat, an F6F-5 Hellcat, a G-63 Kitten, an F9F-7 Cougar, an F14 Tomcat (and cockpit), an A6 Intruder and a long nose F-11 Tiger done up in Blue Angels livery in the Atrium in addition to what is arguably the prize of the collection, the Grumman Lunar Module LM-13 which was built for the cancelled Apollo 18 moon landing.

Other major local manufacturers like Republic are well-represented with a P-47N Thunderbolt, RC-3 Seabee, a P-84B Thunderjet, an F-105B Thunderchief, a Fairchild-Republic A-10 Warthog and a Fairchild T-46 Flight Demonstrator. Other locally produced, though lesser known craft include a Waco CG-4A Glider and a Commonwealth 185 Skyranger.

Locally produced rotorcraft on display at the museum include a Gyrodyne QH-50C, Gyrodyne Model 2C and a prototype Convertawings Model “A” Quadrotor, which was the world’s first 4-rotor helicopter to fly. Missiles produced on the island are also on display including a Maxson AGM-12C Bullpup, a Maxson AQM-37A Target Missile, a Fairchild AUM-N-2 Petrel and a Republic JB-2 “Buzz Bomb”, a design that was turned around and rolling off the production line in only two months after Republic received a a captured German V-1 to use as a template.

More than just a museum, the Cradle of Aviation aims to proactively ensure that Long Island and the nation remains at the forefront of technological advances in aerospace. To that end there are a number of STEM programs organized by the museum and New York State ranging from aerospace-themed birthday parties for the 3-6 year-old set and summer camp programs for elementary schoolers, straight through to interning opportunities for high school students at local defense contractors. The Museum also holds an annual STEM Career Expo onsite and along with the US Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory are the lead organizations of the Long Island STEM Hub which in turn is part of the Empire State STEM Learning Network, which aims to create a pipeline of STEM-literate students to feed industry and to find ways to connect the business with academia and not-for-profit providers of STEM training to help boost both national and regional development of cutting edge technology for today and the future.

More than just a museum, the Cradle of Aviation aims to proactively ensure that Long Island and the nation remains at the forefront of technological advances in aerospace. To that end there are a number of STEM programs organized by the museum and New York State ranging from aerospace-themed birthday parties for the 3-6 year-old set and summer camp programs for elementary schoolers, straight through to interning opportunities for high school students at local defense contractors. The Museum also holds an annual STEM Career Expo onsite and along with the US Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory are the lead organizations of the Long Island STEM Hub which in turn is part of the Empire State STEM Learning Network, which aims to create a pipeline of STEM-literate students to feed industry and to find ways to connect the business with academia and not-for-profit providers of STEM training to help boost both national and regional development of cutting edge technology for today and the future.

The Cradle of Aviation Museum is well worth a trip and dramatically demonstrates that there’s much more to Long Island than just endless traffic and The Hamptons. The museum is open daily Tuesday-Sunday, 9:30-5:00 and is open Mondays during school holidays and breaks.

Be the first to comment

Graphic Design, Branding and Aviation Art