by Sam Worthington-Leese

Getting into warbirds might seem like an impossible dream, akin to being a Formula 1 driver, joining the SAS, or becoming an astronaut. But, there are Formula 1 drivers, there are soldiers in the SAS, and there are astronauts – so it isn’t impossible. Other than time travel, or settling the debate over whether milk or hot water goes first in a cup of tea, very few things are actually impossible (and even time travel has its proponents). Changing your mindset from impossible – to possible – regarding a particular challenge, is probably the first but most important hurdle to overcome. Indeed, most people use the word “impossible” to describe an objective which might, on closer inspection, simply take serious effort, time and dedication to achieve. So while getting into warbirds is rarely easy (except for those with deep pockets) it isn’t impossible.

From a personal perspective, I have wanted to fly Spitfires for as long as I can remember. My grandfather flew them during WWII, after the Hurricane and before the Typhoon; he died when I was young, but I’m sure something of his passion passed from him to me. When I was about six, a little part of me secretly hoped the Battle of Britain might start again, with the naive idea that this could allow me to fly a Spitfire. You could say that my journey started then, or maybe a few years later – about the age of ten – when I taught myself to fly on Microsoft Combat Flight Simulator after school. I flew the Battle of Britain Campaign over and over again; beam attacks, Immelman turns and deflection shooting all seemed so easy at that age.

You might even say the journey started for me when I had just finished college and started glider flying whilst applying to join the Royal Air Force. Flying locally to where I lived above the South Downs, WWII-era bomb craters were still visible on the hills. Glider flying also included my first experiences being close to taildraggers, as we first rose into the air towed behind the club’s Piper Pawnee – a poor man’s Hurricane. But all of this was just wishful thinking, in reality; I wasn’t taking any proactive action on a path towards warbirds. However, that all changed after I joined, and subsequently became redundant from, the RAF. Then, a few months later, the commercial flight school I had chosen went bust, and I became a modular student, with seriously depleted funds. I knew I wanted to fly for a living, but I also knew I wanted to fly warbirds; the two don’t generally go hand-in-hand. So I had to figure out a plan.

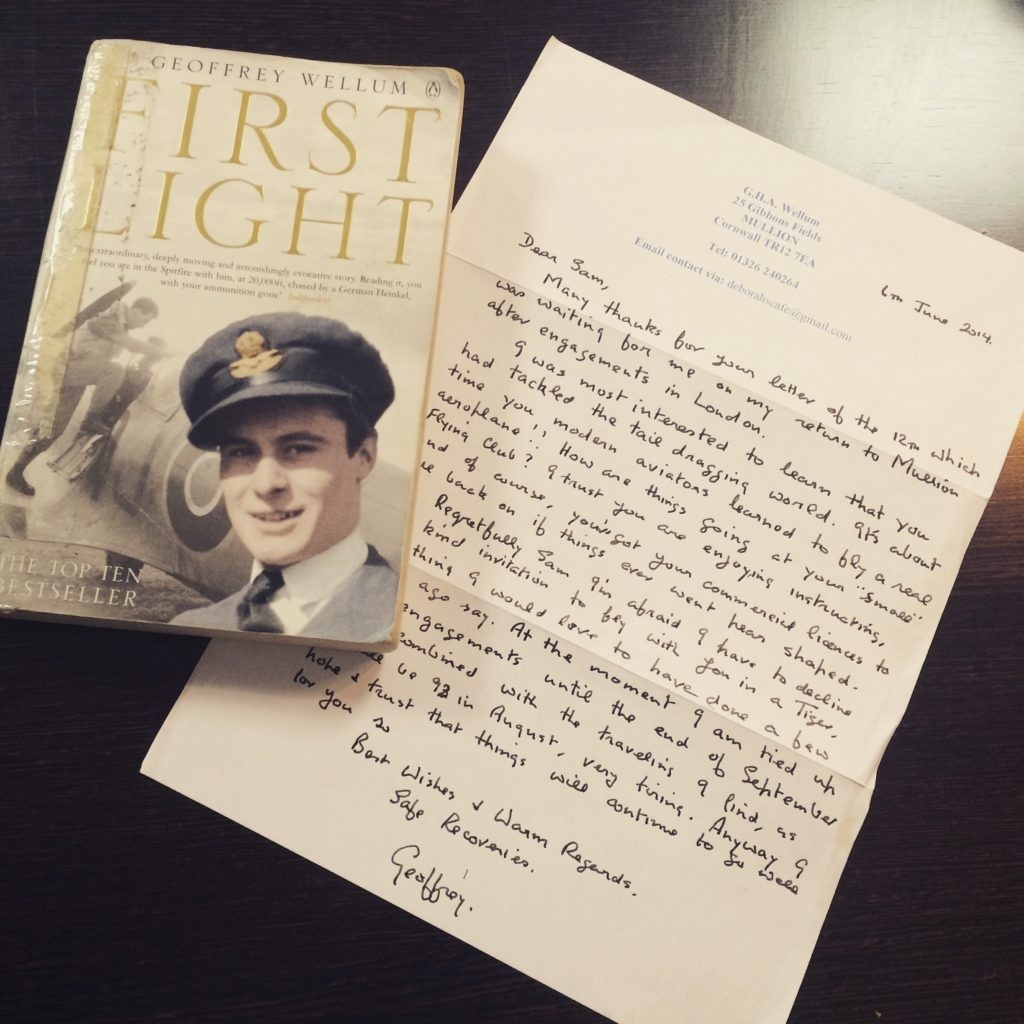

At the time, there was very little information available that I could find describing a path into warbirds, so I just extrapolated what I could find. Once you get to the bottom of it, the requirements for somebody to fly warbirds are actually quite straightforward. The vast majority of warbirds are taildraggers. The pipeline to train young fighter pilots in WWII is there to read about in any aviation memoir from the period, but the one which I found best describes it, at least for me, is Geoffrey Wellum’s First Light. The initial aircraft he flies is the now-legendary de Havilland Tiger Moth. Following 50 to 60 hours of elementary training on these biplanes, he moved on to the more complex North American Harvard. Following about 150 hours of more advanced training on Harvards, Gillum then got posted to No.92 Squadron, to both his and the unit’s surprise; 92 were working up on Spitfires at the time.

Given Gillum’s experience, it seemed to me that if training was like that then, why shouldn’t it be the same now? At the end of the day, the end goal is the same – to fly a Spitfire. This set my mind to work; if that’s how pilot’s transitioned to Spitfires then, then it should work now. Admittedly, the hours requirements might be higher, perhaps double, or even triple, as there isn’t a war on after all. But, with that, I was starting to form the first phase of my plan. I needed to fly something like a Tiger Moth, or similar, and then move on to a Harvard, or similar, before being let loose on a Spitfire. That seemed simple enough; three rungs to the ladder. I had the foundations of a plan!

However, flying those aircraft is very, very expensive; it is upwards of £200 an hour for a Tiger Moth, £700-800 per hour for Harvards and lottery winnings for the Spitfire. Even with my meagre maths skills, I could figure out that those costs were going to be prohibitive as I had no chance of earning that sort of money. But returning to my earlier thoughts that it must be possible, because people do it and they can’t all be millionaires, I had a rethink. During the hour-building phase of my modular training, I completed a tailwheel conversion in a Stampe down on the south coast. The Stampe is a great aircraft, a vintage open cockpit biplane, just like the Tiger Moth, but without all the bad bits. The instructor was a great guy who taught me a lot in those early taildragger sessions.

Hang on a minute – instructors don’t pay to fly, they get paid… Epiphany!

In the final stages of my Instrument Rating which would complete my commercial flight training, I received a call from the CFI at the school where I completed my tailwheel conversion; would I like to “help out for the summer?” As long as I got my own Instructor Certificate, I could expect quite a decent amount of flying. And because I had a small amount of tailwheel experience, I could expect to pick up trial lessons on the Cub, Stampe, and in time, the Tiger Moth. Out came the maths again; the cost of the FI certificate divided by the hourly rate of the taildraggers meant I only needed to get just over 30 hours over the entire summer for it to break even. Coupled with the fact I would be earning a small amount of money whilst flying those hours, as well as flying standard “spam cans” as well, I decided to take the gamble. I had no idea at the time if it would pay off.

The gamble was this – earn next to no money for a given time period, but obtain as much tailwheel flying as I could by doing it full time. I would do this intensely for a few years, build up a base of tailwheel experience, that I could then use in my spare time if and when I got a job with an airline, in say, five years’ time. I was turning down some quite juicy salaries as an airline pilot, and airlines were hiring, but I figured I was still relatively young, could put up with living back at home for a few years, and when might I get this opportunity again?

Two full seasons later at the school, and alongside the more standard flying, teaching PPL students and so on, I had managed to clock just under 300 hours on the Cub, Stampe and Tiger Moth. The best part is that I had only paid for a handful of those hours, when I self hired to take friends or family up, and then they chipped in. I hadn’t made a fortune doing it, far from it, but I hadn’t spent a fortune either. My FI certificate had more than paid for itself and I had got myself onto the first rung of the ladder. If First Light and my plan was anything to go by, the next rung of the ladder was the Harvard. Moving to another school on the south coast at Goodwood, the next step would fall into place.

In all honesty, I didn’t know the flying school at Goodwood owned the Harvard. I thought it belonged to their neighbour, the Boultbee Flight Academy. Deep down, that was my thinking for the move to Goodwood. My grandfather’s last flight of WWII departed from here, but there was a Spitfire operator on the airfield, Boultbee. I thought, maybe, that if I hung around enough they might give me the keys one day. Having been at Goodwood for around three months, flying the Cessnas and the Cub that the flying school operated, the management were scratching their heads a lot about a reliable, and available, pilot for their Harvard as they kept having to turn trial lessons away through the lack of a resident instructor. Picking my time with the flying school manager, I decided not to ask, but just to let him know that I’d be more than happy to help… At this time I had around a thousand hours total, three hundred or so on taildraggers and could teach aerobatics. I even offered to pay for my conversion training, thinking that even if it took me five or more hours, it would be worth it in the long run if I could pick up just a handful of flights. They were clearly well and truly stuck for someone reliable and available, because the answer was yes. What’s more, I wouldn’t pay for my conversion but I would get a reduced rate of pay for flying it for the first year.

And so I moved up to the second rung of the ladder. During this time, I co-founded the Hawker Typhoon Preservation Group, an endeavour I had been working on for a few years already and one that saw me visiting many of the warbird restoration shops in the country and meeting their owners, many of whom operated aircraft as well. I also joined the team at Ultimate High, a great organisation that I had known for a few years, since my hour building, when a friend kindly introduced me to them whilst they were searching for someone to work on some ground school development for them. Now, I was to be a pilot on their team, something which I thought would never happen as they employed exclusively ex-military fast jet pilots. I was ex-military though, just. This was also the perfect time to make use of a contact I made during PPL training, Cliff Spink. With the guidance of Jos and the team at Ultimate High and Cliff, I worked up for, and obtained, my Display Authorisation. Having a DA is not necessarily about flying the displays in the first instance, but I found it incredibly useful to network at shows and do more of getting to know the right people; the rare display flying was a bonus!

Three seasons later, as the sole in-house “full time” Harvard pilot, although self employed and still not earning very much, I managed to pick up 220 hours in the type. Coupled with the DA, three years of flying with Ultimate High and my work with the Typhoon project, I was starting to think that maybe, just maybe, the next rung of the ladder might be around the corner.

Try as I might, no amount of hanging around the Boultbee hangar seemed to have the desired effect. And anyway, they had their own young resident pilot and skygod coming up through the ranks, a good friend of mine Tim, aka Princess. Through my work with the Typhoon, I had met John Romain at the Aircraft Restoration Company a number of times. I had got to the stage where people had stopped asking “who are you?” in the hangar when I dropped in, so I took that as a good sign. I had come to an arrangement with them too, to use their shower early in the mornings when exhibiting on the Typhoon stand for four days in a row at air shows while camping on site. Part of that was simply my need to be clean and presentable for the public, but part of it was also just being there in that environment, having a coffee afterwards and chatting to the team. Cliff Spink was an ARCo pilot and I knew he was keen on new blood coming into the scene to take over from the“old farts” (his words) who would be retiring in the coming years.

Through a Black Tie event for the RAF100 anniversary which the Typhoon project had been asked to supply some material for, I find myself sitting next to Anna from ARCo. Anna runs all the bookings, sorts the pilots and their lives out, and generally organises a lot of what happens there. I’d met Anna once before, although she didn’t remember it, why would she? The seating arrangement was pure fluke, but I was there, and so was she. Talking over dinner and plenty of wine, we spoke about instructing, which we had both done, display flying, people to watch out for, the Typhoon, New Zealand where I had just got engaged and come back from, being vegetarian, all sorts. And then she says they “cannot find Spitfire pilots for love nor money”. Well, what’s the worst that could happen I think to myself?

“I’ll do it”

“Don’t be silly you need loads of tailwheel time!”

“I’ve got about 600 hours of it”

“Yes, yes, but you need Harvard time”

“Well I’ve got about 200 of that”

“OK, but you need a CPL too, for the rides”

“Yep, got one of them too”

Seeing a mild look of confusion on her face, I just smiled and left it at that, we got back to the dinner, other conversation and the wine. I didn’t think much of it until a few weeks later.

Walking into the pub on my own, I saw John Romain, Anna and one other, James, at a table round the corner. I waved, thought nothing more of it and went to the bar. I was due to fly to Duxford to renew my DA on the Friday before the May air show, but the flight got cancelled so I drove up instead to be there to set up the Typhoon stand. That meant I was there for dinner that evening and that was when the gamble that I’d taken all those years ago after working out my plan paid off. Taking my first sip of beer, John came over and apologised for not recognising me in the light and invited me to sit with them for a drink as they were leaving soon.

“How many hours do you have on the Harvard, Sam?”

“About 200…”

“And you have a CPL?”

“Yes…”

“Good. I want you to fly my Spitfire.”

I knew instantly that in the background, although John knew me through the Typhoon, Cliff had been mentioning that the idea of new blood was a good one. Then Anna had come back from the Black Tie dinner and must have mentioned something to John. John had then probably checked with Cliff, probably his old mates at Ultimate High, and all the strands had come together. Of course, I said yes!

To me, getting into warbirds was a dream; it almost still is, thanks to COVID-19. To me, there are three rungs to the ladder – small taildraggers, bigger taildraggers, then the warbirds themselves. Gain as much experience on the first two rungs as possible, however you can do that. For me, instructing worked. Do whatever you can to add to your “flying CV”. For me, two things that played a huge part were being heavily involved in the charity work for the Typhoon project and everything that brought, but so too did having the DA; working closely with Cliff for that was a key link in the chain at ARCo for me.

Patience is also key. When I set out on the journey, I was fully expecting it not to happen, or that it would take ten or maybe twenty years if it did. Had I gone about the vintage flying part time, then it would certainly not have happened yet. You will see the results if you immerse yourself in the scene. Live it, breathe it, do charity work, volunteer for the “rubbish” jobs, get involved as much as possible, drop in when you can, even “just” sweep the hangar floor. A classic inspirational story of that happening is with “Rats”, who is now the Aircraft Restoration Company’s head of training; he had the unenviable job of trying to teach me to fly a Spitfire. After a full career in the RAF, he swept the hangar floor at Duxford for seven years without touching an aircraft. Now though…well, there you go.

Like anything, if you have a plan, and focus everything possible on that plan, or that dream, taking small steps forwards all the time, then you can achieve it. Sure, it will require some sacrifice, but if the end goal is worth the sacrifice, then you’ll do it. But first, you must change your mindset from impossible, to possible!

Sam Worthington-Leese is a professional pilot, instructor, display pilot and mentor. Currently a First Officer with TUI Airways UK, operating the 737, company pilot with the Aircraft Restoration Company, Duxford and instructor with Ultimate High, Goodwood. He is a Trustee of the Hawker Typhoon Preservation Group, a charity established to raise the funds required to rebuild Hawker Typhoon MkIb RB396 to airworthy condition and Director of the all volunteer project team working on achieving the charity’s aim. Founder of pilot396.com a community established to give an insight and guidance on getting into warbirds. For more information about Sam’s mentoring programs visit www.pilot396.com

For more information and to keep up to date with the Hawker Typhoon Preservation Group project, visit the official website at www.hawkertyphoon.com. The Hawker Typhoon Preservation Group also has a strong social media presence – visit them at Facebook , Twitter and YouTube.

Be the first to comment

Graphic Design, Branding and Aviation Art