Carl “Skip” Bell was born at Emory Hospital on August 6, 1945, the same day the B-29 Enola Gay dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima. He said of the coincidence, “How about that, two man-made disasters in one day.”His schooling depended on his father’s postings. “As an Army family we moved a lot,” Skip said. “I attended grade school in Decatur, then went to a grade school in Alabama, then back to Decatur. I started high school in Athens, Greece then finished up in Fayetteville, North Carolina after dad was assigned to the 82nd Airborne.”

Turned down for an appointment to West Point due to lower than required grades, Skip recalled, “My father considered me rebellious enough to be in need of straightening out so North Georgia College was chosen for the task. Dad graduated from North Georgia and since our citizenship was in Georgia I didn’t have to pay out of state tuition. I loved it. Yeah, as a military college it was structured and required discipline, unlike all the things happening with the subculture in the 60s. And yeah, in your freshman year the upperclassmen treated you like you’re two notches below the lowest lifeform on earth, but at that time in my life that’s exactly what I needed. I got the message, and the education.”

Skip graduated from North Georgia with a commission in the regular Army as a 2nd lieutenant in 1967. He went on active duty almost immediately. “I was sent to Fort Jackson, South Carolina to push Army trainees who had more time in army than I did, but my training at North Georgia helped me become the type of leader that was needed. Then I went for my own basic training at Fort Knox. After graduating from basic in October of ‘67 I decided to volunteer for ranger school. Very interesting course to say the least; I went in weighing 167 lbs. and graduated weighing 136 lbs.”

Skip married during his senior year at North Georgia. “My wife was one year behind me at North Georgia and stayed to finish her education while I reported to Friedberg, Germany as scout platoon leader of the 1st Battalion, 32nd Armor, 3rd Armored Division. She joined me in March of 1968, just in time to get pregnant.”Vietnam was embroiled in the 1968 Tet Offensive while Skip served in Germany. He recalled, “The Army Times publication had a center section reserved for a list of casualties, pages of it in small type. We knew people on that list and felt like we needed to go there to do something.” Skip’s daughter was born in February of 1969. In less than two weeks he was ‘boots on the ground’ in Vietnam.

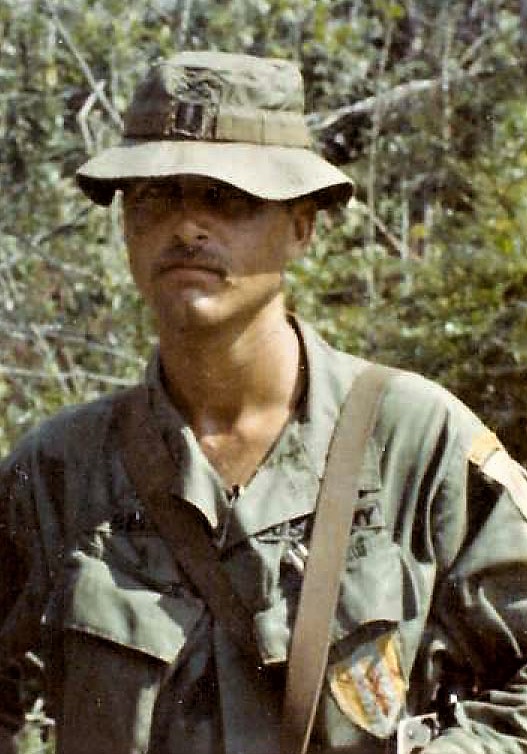

“We flew into Cam Ranh Bay expecting to serve in the northern part of the country,” Skip said. “Didn’t happen. The next day we boarded a plane and flew into Bien Hoa in the central part of Vietnam as replacements. I was assigned to the 1st Infantry Division, 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry as a platoon leader of three 50 ton M48 tanks and seven APCs, or as we called them, ACAVs, Army Cavalry Assault Vehicles.”

Skip spent the next 4 months patrolling, setting up ambushes, and running convoy security. “We protected the Rome Plows (made in Rome, Georgia), big Catapillar-type armored plows used to knock down jungle. If ambushed we fought from our ACAVs and charged into the ambush. We normally stayed on top of the vehicles. It was cooler outside, and yeah, we might get hit by rounds from an assault rifle but you might survive those rounds. But an RPG (rocket propelled grenade) can go through the side of an ACAV like a knife through hot butter. Your chances of survival inside are nil.”

Skip quickly learned from what he called ‘life lesson’ situations. “I remember the day during an ambush how the RPGs targeted the tanks first then tried to hit my ACAV. Why me? Well, I’m riding an ACAV with two antennas as a commander while the other ACAVs only sported one antenna. Fortunately, their aim was horrible.”When asked if an RPG could take out a tank, Skip replied, “Yes, if the RPG hit the right spot. After I left that platoon my former platoon sergeant’s tank took a hit in the thinly armored suspension system. The RPG punched a hole in the tank which set off the ammunition. The driver was killed and the platoon sergeant blow out of the tank. I guess an RPG was the weapon I feared most, very deadly.”

After 4 months ‘in-country’ Skip was named Squadron Supply Officer, S-4. “The guy before me did a lousy job. We were short on uniforms and supplies, so I was picked for the job. After 6 weeks I told my boss that I didn’t come to Vietnam to push supplies. I’d asked for an advisor position with an ARVN unit based near us but my boss told me to stick with him so I did. Well, a troop commander was killed shortly after that and I was sent to replace him. I took over Bravo Troop for my last 6 months in Nam.”

Skip was a junior Captain but the most experienced. He said, “The old man wanted someone who knew how to operate, so he left me there. We suffered several KIA and WIA but we got a lot more of them than they got of us. At that stage of the war that’s how they measured success.”The quality of his soldiers? “They were great soldiers, mostly draftees, but I can’t say enough about my men. As an armored unit we had it better than the infantry but not as good as the guys back at the base camp. We rarely got out of the field, we camped out all the time, but at least we could sleep on or in the vehicles and we didn’t have to carry what we owned. As I said, we usually stayed atop our ACAVs and seldom dismounted. By the way, 5 of us officers have a reunion every year, 4 of which suffer from cancer, diabetes, or both, from exposure to Agent Orange.”

The explanation: “We were in the heaviest defoliated area in Vietnam, northwest of Saigon between the Capitol and the Cambodian border. We’d set up ambushes at the edge of the Rome Plow cuts since the enemy would plant booby traps in that area knowing the plows would be working it the next day. As a result, the cuts along roads and jungles would be heavily defoliated. We were lucky to get anything resembling a bath for weeks so Agent Orange remained on our uniforms.”

Rome Plows created creature problems: “The plows destroyed part of the eco system so at night the homeless wildlife would leave the area. As a leader I did a lot of what-ifing, what if this happens, what if that happens, especially when you only have split seconds to make decisions. Thing is, a lot of the animals leaving the plowed areas weren’t born with legs, like reptiles. That meant ‘what-if’ a Cobra or other venomous vermin crawl up my pants leg as a firefight begins. I never figured out that what-if, but thank the Lord it never happened.”

December 7, 1969: “We spotted some abandoned huts and the lead guys started dismounting to investigate. They ran into booby traps. Then the second group of guys dismounted to help the first guys and they also ran into booby traps. I knew from experience there would be a third area booby trapped. Well, I’m jumping from the vehicle with a radio in hand talking to a medevac. Another dismounting trooper lands on a booby trap while I’m in mid-air and the explosion throws me back against the vehicle but I keep talking to the medevac.

He comes back, ‘Hey, are you hit?’

I answered, ‘Yeah, I think so.’

He comes back, ‘I thought you were, your voice just went up about 8 octaves!’

“Well, it was funny then, even with shrapnel in my face and nose. The medevac took out the badly wounded but the walking wounded, including me, stayed, got patched up, and remained in the field.” Skip’s face was treated but shrapnel is still in his nose.

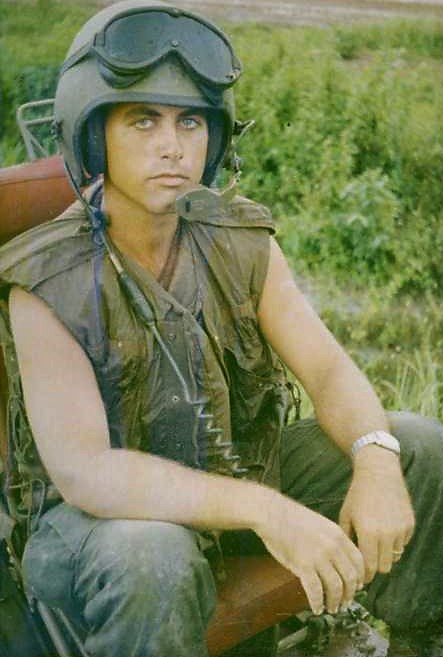

Skip returned home in February of ’70: “I was assigned to Fort Benning to teach armor tactics but was first required to take an infantry officer advanced course. So I’m sitting there with bleeding leech bites and weighing about 140 lbs. next to guys who were Army aviators in Nam. They’re in great shape, had loads of money, and seem happy as heck. And I’m thinking, ‘shoot, maybe there’s a better way to do this Army thing.’ I decided to take an aptitude test and physical to qualify for pilot training. I passed both and ended up going to flight school.”

Primary training was at Fort Walters, Texas on TH-55 Osages. Then on to Fort Rucker, Alabama to pilot HU-1B and HU-1D Hueys before transitioning to Cobra gunships at Hunter Army Airfield in Savannah, Georgia. Comparing a Huey to a Cobra: “Like moving from a sedan to a sports car.” Back to Vietnam, 1972: “I reported to the 1st Aviation Brigade Assignments Officer who happened to be a classmate of mine at North Georgia. He asked me, ‘Where do you want to go.’ I replied, ‘Where’s the war?’ He replied, ‘The Delta,’ so that’s where I went.”

Vinh Long in the Mekong Delta: “I’m flying Cobras out of Vinh Long for about 2 months when they receive orders to pull out, like so many units were doing by 1972. They were heading to Hawaii. I volunteered to go. ‘Nope’, I was told, ‘You’re staying here.’ So, I end up at Can Tho on the south bank of Hau River, a distributary of the Mekong River, flying Hueys for the 18th Corps Aviation Company. We had one platoon of Chinooks and a platoon of OH-58s plus two platoons of Hueys. We flew in support of MACV advisors, going to different provinces, really good flying. Medevac missions when required, resupply, ash and trash, everything from pigs and chickens to ammo and food, whatever and whenever.”

On missions into Cambodia: “We flew support for convoys plus flew into the Cambodian Capital of Phnom Phen occasionally to pull embassy flight assignment duties. We dodged a few RPGs and small arms fire but it seemed like they weren’t trying very hard to hit us. I remember a mission when I was flying a Cobra and we landed to hot refuel at a ferry sight called Neak Long on the Mekong River. A hot refuel meant the gunner stays aboard while the back seat driver helps fuel with rotors going. I look across this field and see warehouses, just roofs on stilts, with pallet after pallet of Coca-Colas stacked a mile high out there in the middle of nowhere. I thought that was a little weird.”

Enter the beast: “I was flying in the western part of the Mekong Delta when we heard the news over the radio that we’d lost a Cobra to a SA-7 shoulder fired heat-seeking missile. I felt a cold chill deep in the pit of my stomach. We had no defense against SA-7s. The only thing we could do is fly map of the earth, that’s hugging the ground, if we knew an area had SA-7s. AK-47s were still a threat but normally didn’t have time to respond if we were flying fast and low, but we’d rather have them shooting at us than an SA-7. You’re talking a speed of .9 Mach, signature like a puff a cotton on the ground, easily capable of severing the tail boom from your aircraft. IR suppression kits were eventually installed on the Hueys which helped some, but the best tactic was still hugging the earth.”

Spring Offense of 1972: “By that time I was working the G-3 shop as a ‘lessons learned’ officer. The NVA had introduced what’s known as a sophisticated anti-aircraft environment, all sorts of deadly weapons, and each one of our fighting units were using different tactics to evade these weapons. So, I flew on these missions to learn and hopefully live. I contributed to the Army’s map-of-the-earth manual and ended my days in Vietnam at the Tan Son Nhut MAVC annex. Fairly safe, and a soldier can really learn to appreciate a clean dry bed.” Skip received a ‘Dear John’ letter during his second tour. “Yeah, I came home a single person but it wasn’t her fault. I was a lousy husband, chasing a career and the bad guys. I ended up at Fort Still, Oklahoma and met a lady I would eventually marry. I was sent back to Atlanta for graduate school at Georgia State and earned a Master’s in Information Management. After that some of my assignments included Fort McPherson and I was also selected to attend the Air Command and Staff School at Maxwell Air Force Base but was unable to attend because of family health issues.”

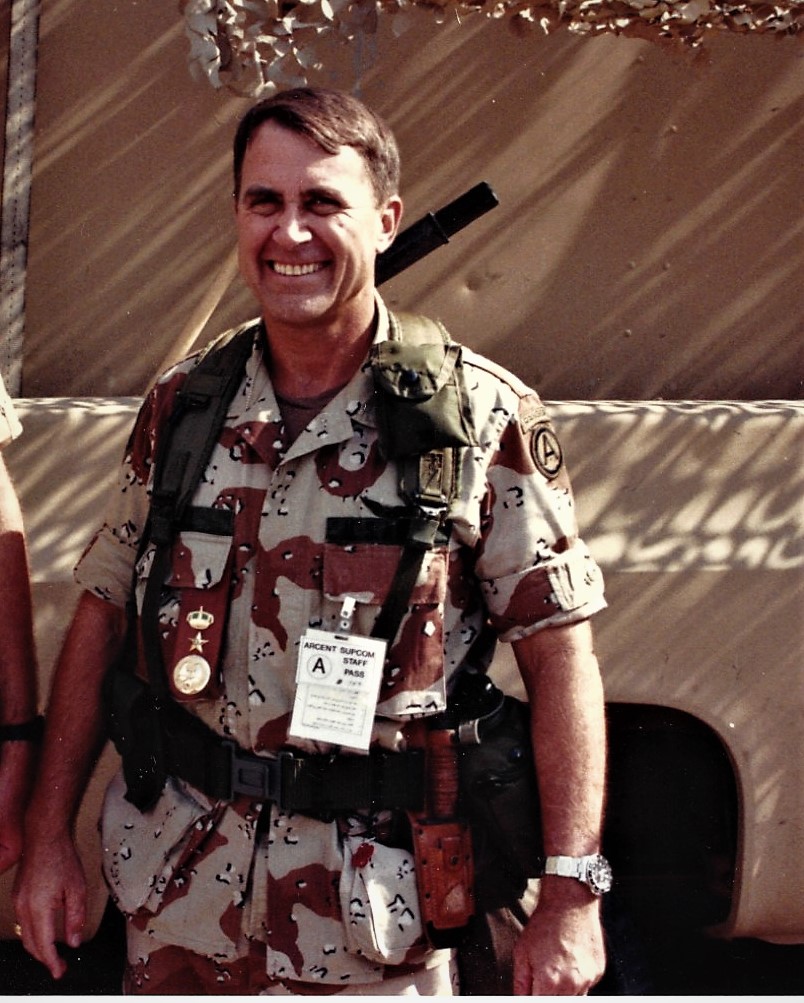

Carl ‘Skip’ Bell served in the regular Army for 14 years. Due to the family health issues he resigned from the regular Army and took a commission in the reserves for another 17 years, which included a deployment to Saudi Arabia during the Gulf War. He retired as a full bird Colonel in 1998, worked for a few Beltway Bandits (government contractors who supply people to handle jobs that the military may not have personnel to perform) and became a full time caregiver to his wife in 2009.

Commenting on the new Ken Burns documentary ‘The Vietnam War’, Skip stated, “I had high hopes for the documentary but it disgusted me. It’s not the true story or the whole story. And it saddens me that this documentary may end up being a defining film about Vietnam. We deserve a lot better.”

To understand Skip’s last comment would require ‘boots on the ground’ experience in Vietnam. The majority of my brothers and sisters from that war faded back into society and for the most part remained silent. Nobody wanted to hear our story. Now, due to long overdue recognition, 4 out of 5 men claiming to be Vietnam veterans are not, according to a government census. It’s called Stolen Valor. That truism is a depressing inheritance for a generation of very brave Americans.

Pete Mecca is a Vietnam veteran. For story consideration visit his website at aveteransstory.us and click on “contact us.”

I was with the 334th at Bien Hoa then Phu Lou 04/70 to 04/71 in avionics