A dismal 25% of B-17 and B-24 bomber crews completed their 25 required missions during the initial phase of the Allied air war over Europe. The mean average was 15 missions before being shot down, killed, wounded or captured. Crew members had a one-in-four chance of going home. Arlie Aukerman completed 25 perilous missions as a nose gunner on a B-24 Liberator including a 1,300 plane raid over Berlin, Germany on March 18, 1945. A member of the 453rd Bomb Group, Aukerman fought the war over Europe in good company. Among them: Oscar winning actor Jimmy Stewart piloted B-24s and future actor Walter Matthau served with a ground crew in the 453th at the Old Buckingham RAF Base near Attleborough, England.

Aukerman was born into the agriculture community of Jackson, Michigan in 1922. Recalling life down on the farm, he said, “We raised our own food and livestock. I did the milking and churned butter. Mom canned tomatoes and peaches and other good stuff. We had no indoor plumbing and no electricity.” Their ‘soft’ water was rainwater caught running off the roof. Aukerman called to mind, “Ma had a cook stove in the kitchen and always had a hot meal on the table for Pa, the three boys, and two adopted girls.”

Extra money was earned driving a team of horses in a hay field for 50 cents a day, plus a hot meal. “Fifty cents went a long way back then,” he said. “We could go to a movie, buy a Coca-Cola and snacks, and still have money left over. When we caught one of the rats running around inside the theater we got free tickets for next week’s movie.”

After high school graduation Aukerman worked a variety of jobs: carpentry; concrete work in the summer; delivering coal in harsh winters; cleaning slag and unloading pig iron at coal mines. He said, “Pa was proud of his boys. We never accepted welfare or handouts. We made our own way.” Married in 1940 and the father of a son, Aukerman avoided the draft until November of 1943.

He was inducted into the service in Detroit, Michigan then sent to Chicago for marshaling. “I did so well on the I.Q. test they assigned me to the air corps,” Aukerman stated. Basic training took place at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, better known as Pneumonia Gulch. After basic the Army sent him to Butler University in Indianapolis. “I joined the CTD, college training detachment,” he said. “I was going to be a pilot, bombardier, or navigator.” Disappointment lay ahead: all of the draftees were pulled out of CTD for gunnery school.

“Yeah, that was a bit discouraging,” he admitted. “I was sent to Harlington, Texas for gunnery training but at least I was in good company; Clark Gable was training there too, or so I heard. I never saw the guy.” Aukerman flew on his first B-24 bomber in Mountain Home, Idaho, before going to Topeka, Kansas for additional schooling. He explained the daily routine: “We rode in back of pickup trucks and fired at moving targets plus practiced field-stripping .50 caliber machine guns while wearing thick gloves. When you’re flying at 20,000 feet the temperature is 20 or 30 degrees below zero so wearing the gloves prepared us for the reality of combat.”

After mastering the Emerson gun turret, Aukerman was finally assigned to a crew. “We were typically American,” he said. “Two Jews, a German Dutch, Yanks and Rebels, and a top gunner from Kentucky. The guy earned a living as a bootlegger and drank a fifth of whiskey every day.”

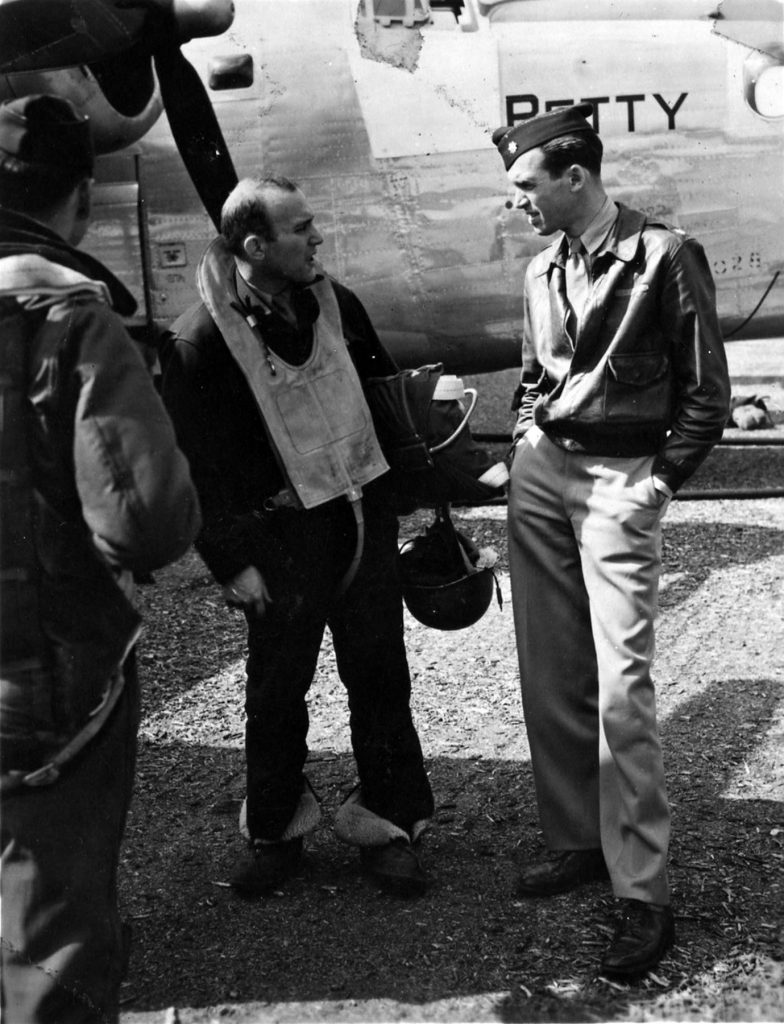

Once training was completed Aukerman sailed from New Jersey aboard the Isle de France luxury liner to Glasgow, Scotland, then went overland to Old Buckingham RAF Base on the coast of the North Sea. The routine became, well, routine: Up at 0200, breakfast, briefing, boarding a B-24, usually the Silent Yoakum. “The actor Jimmy Stewart flew in the same squadron,” Aukerman said. “He was a regular type guy and took his chances just like the rest of us. We had a lot of respect for Jimmy.”

After takeoff the bombers formed into ‘bunchers’, flying in circles at prearranged altitudes until properly positioned in formations. “That was a scary part,” Aukerman said. “We usually lost two or three planes during the procedure.” From the nose gunner’s front-row view, Aukerman witnessed one B-24 clip the tail off another B-24. “Nobody made it out,” he said. One B-24 with a full bomb load and 2500 gallons of aviation fuel didn’t have the power to successfully take off. “It ran off the end of the runway and exploded in a gigantic fireball,” Aukerman recalled. “Nobody even checked for survivors because we knew the crew couldn’t survive that kind of crash.” To everyone’s twinge of guilt, one of the crew members had survived. Aukerman said, “They found the guy the next day. He’d crawled into a ditch and died of exposure overnight.”

One incident had Aukerman believing the Grim Reaper had arrived for his soul. “We were forming benchers,” he said. “The sun was directly behind us so our shadow reflected on a bank of clouds in front of us. It looked like another B-24 was heading straight into us with no time left to react. In a split second we hit the cloud, but, thank the Good Lord, not another B-24.”

Their targets were varied but all dangerous, as noted on a mission sheet: Mayen: the Marshaling yards in town, 2000 planes on raid, lost 35. Neuwied: the Rhine River Bridge, lost two planes from formation, missed target by two miles, crash landing upon our return due to crosswise nose wheel. Rheine: Marshalling yards, feathered #3 engine 34 minutes from target, lagged formation, returned alone. Gielbelstadt: Jet Airfields near town, awarded citation for best bombing in 8th AF, worst flak ever encountered, 15 holes in plane, four hits in one wing. Berlin: Anti-aircraft factory, unbearable flak, 1300 planes in the raid, lost 24 bombers and six escort fighters.

Aukerman had too many close encounters with the deadly Schwalbe, meaning “Swallow” in German, better known to the Allies as the Me-262 German Jet Fighter. The Me-262 was the first operational jet fighter in history and made its debut in mid-1944. With a top speed of 559 mph, the jet fighter was years ahead of the prop-driven Allied fighters and their vulnerable bombers. Approximately 545 Allied planes fell victim to the deadly Schwalbe, but American fighter pilots quickly learned the new jets were vulnerable during takeoffs and landings. Aukerman said, “It was too fast for us to draw a bead on,” he said. “By the time you saw it, it was gone, but our P-51 escorts would drop their fuel tanks and dive after the jets. They bagged quite a few with that maneuver, but our planes couldn’t turn with them at high speed. For Germany and Hitler, the Me-262 was too little too late, but one of the best fighters of the war.”

Having completed 25 missions, Aukerman’s crew members were sent home for various assignments. But Aukerman, having studied to be an engineer, was sent to Alma Gordo, New Mexico to train as a flight engineer on a B-29 bomber. Albeit, the two atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki probably saved his life. He said, “There’s no doubt I would have been part of the Invasion of Japan. I was thankful that America developed the ‘bomb’ first, and yes, thousands died in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but those two bombs saved an estimated one million Allied lives and an estimated 10 to 20 million Japanese lives. Think about that, a spread of 10 million lives lost had we invaded the Japanese mainland. I don’t think either side wanted to see that kind of carnage.”

After the war Aukerman returned to the concrete business. Times were good; the nation was rebuilding and reviving itself. Aukerman invented then patented a variable screed, a contraption that enables highway contractors to quickly construct concrete medians separating traffic on interstates. Approximately 90% of concrete poured into the interstate system circling Atlanta was poured by A. C. Aukerman Company.

After his first wife was lost to a heart ailment, Aukerman met then married his present wife, Frances, in 1980. As a couple they renovated an old farm house into an elegant antebellum home in Lovejoy, Ga. They also discovered a long forgotten Confederate cemetery on the new property. He stated, “You know, Hitler caused the deaths of many brave men, and it’s an ironic note to history that the S.O.B. took the coward’s way out. And let me close with this, we are known as The Greatest Generation but we just did what we had to do, and thankfully we did it well.”

Well done, sir, very well done. B-24 nose gunner Arlie Aukerman reported for his final inspection on January 22, 2017.

Pete Mecca is a Vietnam veteran. For story consideration visit his website at VETERANSARTICLE.COM and click on “contact us.”

Be the first to comment

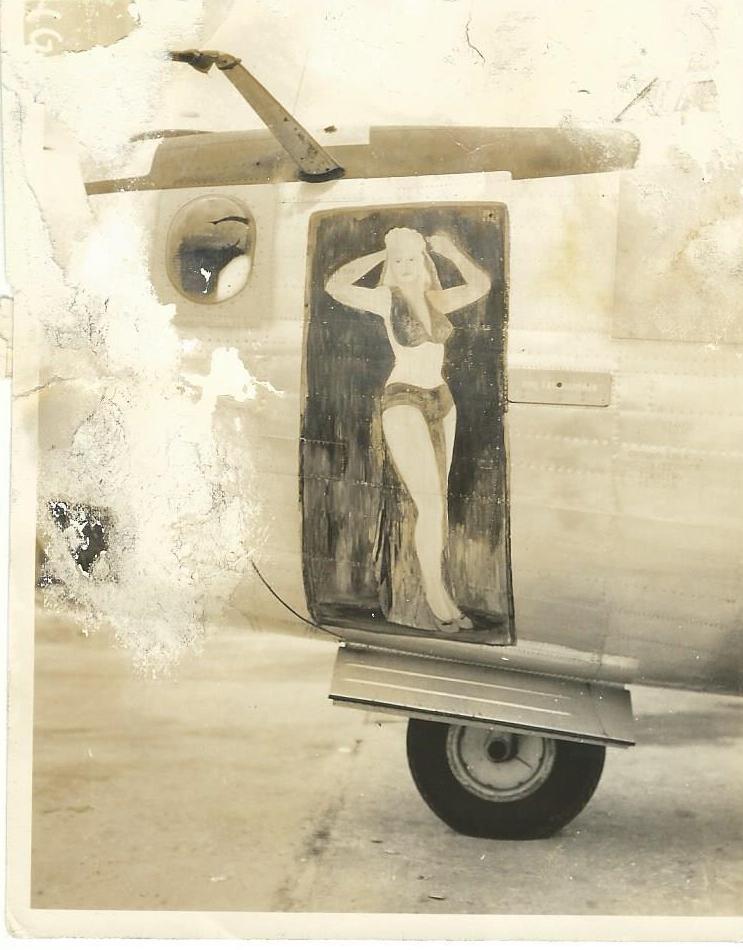

Graphic Design, Branding and Aviation Art