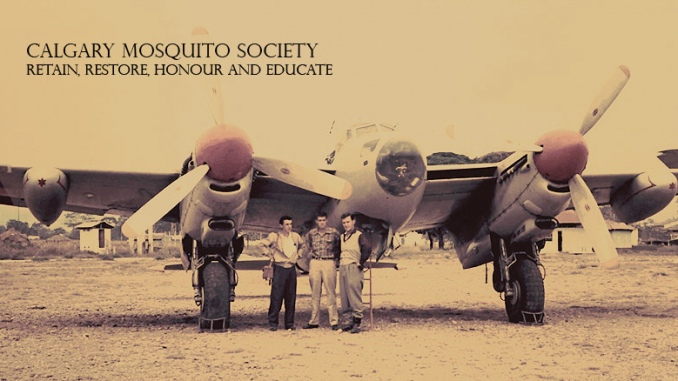

If we had to name one warbird that has grabbed headlines this year, it has to be the de Havilland Mosquito. From the historic airworthy resurrection of a Mossie, orchestrated by Jerry Yagen and the Military Aviation Museum of Virginia Beach, Virginia, the restoration of another to flying condition by Victoria Air Maintenance, near Victoria, Canada, or the still-nascent efforts of The People’s Mosquito project in the UK, which recently had the remains of a long-buried Mosquito donated to the cause and, like the Yagen Mosquito, will likely make use of a new wooden fuselage, fabricated from scratch by Glyn Powell of Papakura, New Zealand. Another Mosquito restoration effort is underway in Nanton, Alberta, a joint venture between the Calgary Mosquito Society and the Bomber Command Museum of Canada, and it’s a project that has had more than its share of controversy.

If we had to name one warbird that has grabbed headlines this year, it has to be the de Havilland Mosquito. From the historic airworthy resurrection of a Mossie, orchestrated by Jerry Yagen and the Military Aviation Museum of Virginia Beach, Virginia, the restoration of another to flying condition by Victoria Air Maintenance, near Victoria, Canada, or the still-nascent efforts of The People’s Mosquito project in the UK, which recently had the remains of a long-buried Mosquito donated to the cause and, like the Yagen Mosquito, will likely make use of a new wooden fuselage, fabricated from scratch by Glyn Powell of Papakura, New Zealand. Another Mosquito restoration effort is underway in Nanton, Alberta, a joint venture between the Calgary Mosquito Society and the Bomber Command Museum of Canada, and it’s a project that has had more than its share of controversy.

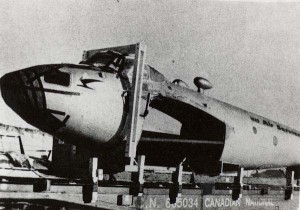

Mosquito fuselage.

(Image Credit: Canadian Historical Aircraft Association)

Arguably one of the most effective and versatile planes of the Second World War, Mosquitos post-war fell victim to the inherent weaknesses of the materials from which they were built. The Mosquito’s unique glued balsa and birch wood construction, conceived to minimize metal usage during wartime, made for an extremely lightweight plane, that while an exceptional performer, had no shot at longevity as the animal glues that held their molded wood fuselages together made for a plane that literally decomposed, and with alacrity if exposed to the elements. Of 7,781 Mosquitos that were produced, only 30 are known to remain in the world today, and of this writing it is only the recently unveiled Yagen Mosquito that is in flying condition.

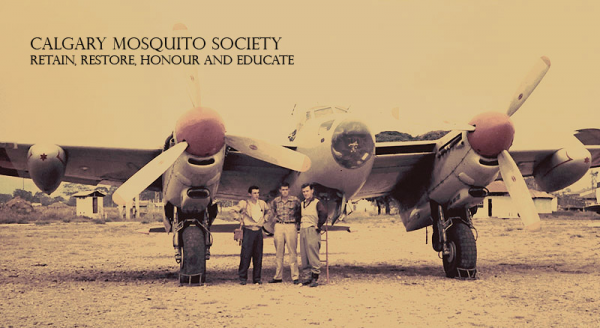

Now known as “The City of Calgary’s Mosquito,” de Havilland Mosquito s/n RS700 was constructed as a B.35 variant by Airspeed Ltd. at Hampshire, England in 1946. The war in Europe over, the plane bounced between various Royal Air Force Maintenance Units before undergoing conversion, becoming the prototype of the PR.35 high-altitude, pressurized, photo-reconnaissance aircraft in 1951. The plane was then assigned to operational status with the RAF’s No. 58 Squadron in 1952 and after just two years was declared surplus and placed in storage, awaiting a buyer.

sometime in the ’50s

(Image Credit: Calgary Mosquito Society)

In 1955, RS700 was purchased by Canada’s Spartan Air Services along with 15 other B.35 Mosquitos, reportedly sold by the RAF for $1,500 a piece. Spartan Air Services specialized in civilian aerial photographic surveying, and the B.35 was the perfect plane for such activities. Five of the planes were broken up for spares and 10 were modified for Spartan’s specialized needs. Modifications of the Mosquito fleet for their new civilian role was performed by Derby Aviation Ltd, at Burnaston Airfield in Derbyshire, UK and the planes were then ferried back to Canada using the same routes that so many Canadian-built warplanes had taken heading east across the Atlantic in support of the war Allied war effort in Europe. Modifications to the Mosquitos included the installation of a large additional fuel tank, installed in the bomb bay, an extra-clear perspex nose cone, a DF loop and a modified rear hatch for the cameraman. RS700 was then assigned the Canadian Registration of CF-HMS.

(Image Credit:Robert Morgan CC 3.0)

(Image Credit: Calgary Aero Space Museum)

(Image Credit: Calgary Aero Space Museum)

shows signs of several fabric repairs.

(Image Credit: Calgary Aero Space Museum)

(Image Credit: Calgary Mosquito Society)

(Image Credit: Peter Cromer/Calgary Mosquito Society)

(Image Credit: Calgary Mosquito Society)

(Image Credit: Peter Cromer/Calgary Mosquito Society)

RS700 served with Spartan from 1956 to 1960, performing high altitude aerial survey operations all across Canada and as far afield as Columbia and the Dominican Republic. In 1963 the plane was sold to controversial Canadian aviation enthusiast, and founder of the Calgary International Air Show, Lynn Garrison, who had assembled a large collection of notable warbirds for his ultimately disbanded, Air Museum of Canada. The plane was on loan from Garrison to the museum, Garrison retained ownership of it and the 30+ other planes that were on exhibit, an unusual arrangement that would become important later. Garrison had the plane disassembled by volunteers from de Havilland Canada and it was shipped on two flatbed train cars from Ottawa to Calgary, with the transportation costs donated by Canadian National Railways. The plane was then stored out in the open at an oilfield pipe storage yard belonging to the Shell Canada where it sat for three years.

In 1968, the plane received some indoor storage courtesy of the RCAF 403 (Reserve) Squadron who kept the plane under cover in a disused mess hall, wheeling the plane outside when the space was needed for social events. In the early seventies, the plane was moved again, this time to a hangar owned by Field Aviation Ltd. and well-intentioned but inexperienced volunteer air cadets did their best to get her cosmetically cleaned-up, stripping off the plane’s tattered fabric coverings. Garrison left Canada in the 1970s, and the collection of his museum was sold by an employee of the museum to the City of Calgary.

In 1988 the plane passed to the successor organization of the Air Museum of Canada, the Aero Space Museum of Calgary, a museum founded in part to house the city’s collection of planes. In 1989, the Mosquito was moved to CFB Cold Lake, where it was to be restored by military volunteers, though the reassignment of the service member who was to be the project leader ultimately scuttled the project, and a year later the plane was shipped back to Calgary with no appreciable work having been done.

In 1992, Garrison, who had long been residing outside the country, contending that he had “loaned” his planes to the City of Calgary for the enrichment of the public of Calgary, was alarmed to discover that the city had been quietly selling off the collection, dispersing his warbirds to collectors across the globe. Garrison brought a suit against the city, seeking to stop the sale of Avro Lancaster FM-136 to the Commemorative Air Force, forcing the city to discuss the fate of the planes which they possessed, but Garrison believed he still held legal title to. Prior to the court date, according to Garrison, he and the city reached an agreement that the planes he had left for the people of Calgary would remain in the city.

The Mosquito languished in storage for another 20 years in a leaky city-owned warehouse, meanwhile pressure to sell the craft again mounted. In 2008, the city was approached by a British aircraft restorer, Peter Vacher, with a unique proposition involving the Mosquito and another plane the city had in pieces, a historically significant Hawker Hurricane which was also in desperate need of restoration. Vacher would take possession of both planes, and ownership of the Mosquito. The planes would be shipped to the UK and Vacher and his crew would restore the Mosquito to flying condition, and name it the “City of Calgary” Mosquito. He also promised to, at least initially, paint the Mosquito in the Spartan Air Services paint scheme and bring it to Canada for an air show season for Canadian aviation enthusiasts to enjoy. He would also restore the Hurricane to to taxi-able condition for the museum and to make an endowment of $1 million available to the city or the Aero Space Museum of Calgary. It seemed an eminently reasonable offer. Ultimately however, Calgarians would have none of it, and facing the potential loss of a significant piece of Canadian Aviation history, the local aviation community became mobilized to not only keep the Mosquito, but to find a way to finally get the plane restored.

arrives at Nanton for restoration.

(Image Credit: Bomber Command Museum of Canada)

(Image Credit: Calgary Mosquito Society)

where she will be restored

(Image Credit: Calgary Mosquito Society)

At a special committee meeting held in March 2010, supporters of the Vacher proposal voiced their opposition to spending $1.6 million of taxpayer money restoring both aircraft, while supporters of keeping the Mosquito stated that the sale of the plane would violate the Canadian cultural properties and import/export laws. The public outcry against the “behind closed doors” sale of yet another historic Canadian aircraft, the fact that any sale would probably violate the cultural properties export laws of Canada, and the demonstration of motivation displayed by the more than 400 people who created and joined the Calgary Mosquito Society showed that Calgarians did have indeed have a strong interest in keeping the Mosquito in Calgary. The committee directed the administration to solicit proposals to restore the aircraft with the hope of keeping the historic planes local.

In 2010 the Calgary Mosquito Society entered into an arrangement with the Bomber Command Museum of Canada, itself a grass-roots community museum that has developed significant expertise in restoring vintage warbirds. The agreement includes the use of the museum’s shop space, specialized tooling and their member’s expertise in exchange for allowing visitors to the facility the opportunity to see a de Havilland Mosquito up close and “in the flesh.” The Calgary Mosquito Society, in its proposal to the city, offered to pay the full cost to restore both the Mosquito and the Hurricane, but when the committee of the city council finally decided the fate of the Mosquito and Hurricane in December 2011, in deciding to partner with the non-profit Calgary Mosquito Society, the city, unasked, agreed to pay for half the estimated cost of the restorations, matching all donations to the society dollar for dollar! The Mosquito, in limbo for nearly 50 years, was finally on the road to restoration and once completed will finally go on static display in Calgary as originally intended.

The Calgary Mosquito Society is actively seeking donations to fund the restoration of the Mosquito and the Hurricane which is being restored by Historic Aviation Services. Thus far, through the tireless efforts of society members and the dollar for dollar matching by the City of Calgary, they need to raise $350,000 by August 1 2014, and donations are tax deductible (non-Canadians, consult your tax advisor). The restoration of the Mosquito promises to be quite interesting, and is expected to take five years. We’ll be sure to keep you updated on its progress.

Neat article.

403 Squadron disbanded March 31, 1964 so someone else sheltered Mosquito.

I had a friend who flew the Mosquito on Pathfinder ops, 2 tours. Graham Smith, with North Hill news and one of my first and greatest supporters. I wanted the aircraft in his colours. The idea of Spartan colors is meaningless to me, but that doesn’t matter. The only important. Thing is it’s retention in Calgary.

I think the Nanton people have a collective conscience that will prevent its sale. My hometown has no conscience. Those who should have protected the 64 aircraft I left dispersed them worldwide for personal profit. Wham my Lanaster FM-136 was going to the CAF I stepped in. My Hurricane now flies under false ID as G-HURI and my Spitfire AR614 is in Paul Allen’s collection.

Amazingly, a guy suspected of selling a lot of my collection, and who slandered me over the years – Richard deBoer now heads the Mosquito restoration project.

I gues the old saying “It’s an ill wind that blows no good.” fits the situation.

I wish them good luck. A pity dozens of aircraft are displayed elsewhere.

Lynn Garrison

haitipro@bellsouth.net

It is my belief that the aircraft needs to be flown to events. Not everyone will go to see a static display.